In his book India Psychedelic: The Story of a Rocking Generation, Sidharth Bhatia recounts how India in the 1960s was pushing against all odds to birth a culture of rock music.

At Shanmukhananda Hall in Mumbai, where a band competition called Simla Beat Contest took place, he describes young Indians gathering for a show that was perilously put together. “Electric guitars were almost impossible to find, and amplifiers were even rarer; enterprising musicians managed somehow with tricks that would be laughed at today, such as using a valve radio or even PA systems better suited to public meetings rather than for music. Local guitars, such as ‘Givson’ (whose name bears a close resemblance to the iconic Gibson), manufactured in Calcutta, were available but hardly comparable to the real thing. Very basic drum sets were made in local workshops,” Bhatia writes.

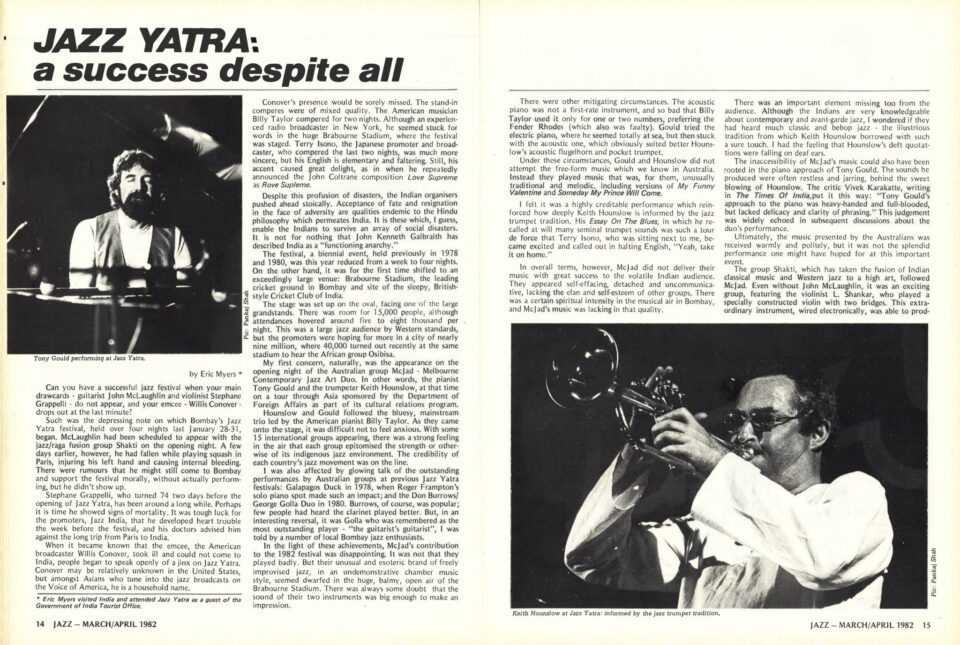

Inspired by the iconic Woodstock festival of 1969 in the U.S., a music festival called Sneha Yatra was held on the outskirts of Mumbai in 1971. Featuring backdrops of instruments, hippie-like caricatures and typography that was downright groovy, it reflected the Flower Power-inspired aesthetic seen in the U.S. from the Sixties onwards. In 1978, Jazz Yatra came to the front, and later led to festivals like Jazz Utsav.

Described as India’s first jazz festival, Jazz Yatra was held at Rang Bhavan with generous help from travel partners like Air India, who covered flights, and support by the American consulate and embassy. Through the latter’s push, jazz greats like Sonny Rollins, Wayne Krantz, Larry Carlton, and Stan Getz made their way to India.

Rolling Stone India Contributing Editor and Jazz Yatra team member Sunil Sampat says the atmosphere at Rang Bhavan was a sight to behold. “People would come with their whole family, it would be like a picnic. One guy would come with an ice cooler, his driver or help would bring that heavy cooler. After a while, the cooler would be opened, drinks would flow, you could have your alcohol. Somebody brought some samosas and pakodas, and you’re just sharing it with everyone. It was a great way enjoy to jazz,” Sampat recalls.

He says it didn’t matter so much if people didn’t enjoy the sometimes esoteric, obscure forms of jazz being hosted. Jazz Yatra went on to set a precedent for jazz festivals in New Delhi and Kolkata. More than that, Sampat recalls that the connection between the organizer, the artists and the audience was completely different. “All the musicians were accessible to you as an audience member. Some of them would finish their set and come sit with you in the audience to enjoy the rest of the concert,” he says, noting how any barriers between the two were dismantled.

Rang Bhavan would cost about ₹800 rupees to rent out in the Seventies and an additional ₹200 would go into renting chairs for a seated audience.

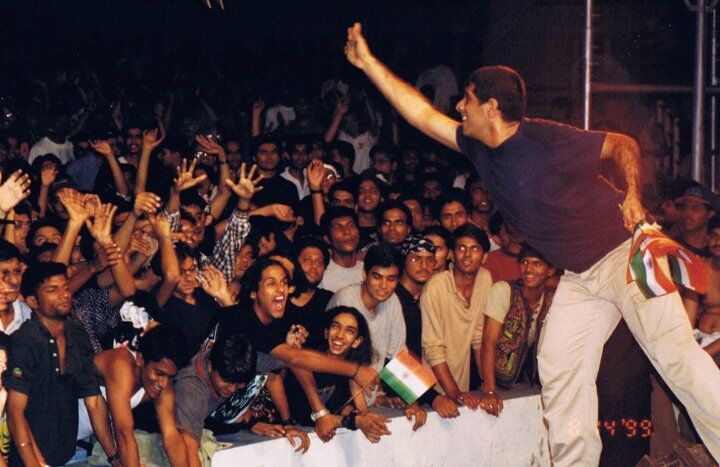

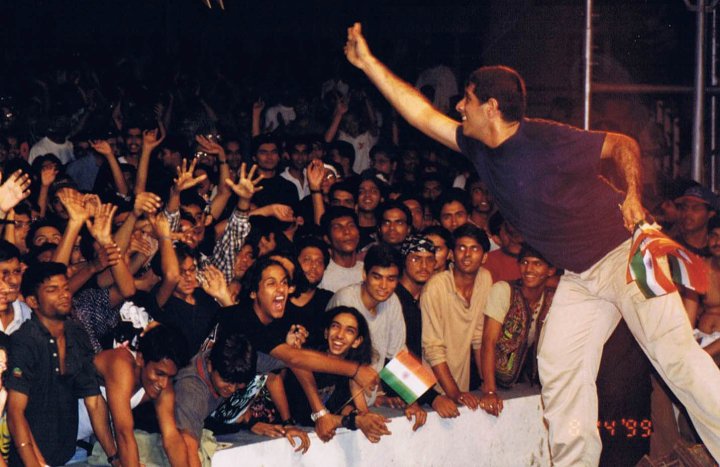

By 1985, Rang Bhavan became the home of rock in India, mostly thanks to gig organizer Farhad Wadia setting up Independence Rock. It was largely about giving bands a stage and giving audiences a space to watch a band live, which was often where the concert experience began and ended in its initial years. Later, with sponsors coming in and the venue shifting to Chitrakoot Grounds in the 2000s, there was more activity around the festival grounds, including sponsor stalls and the like.

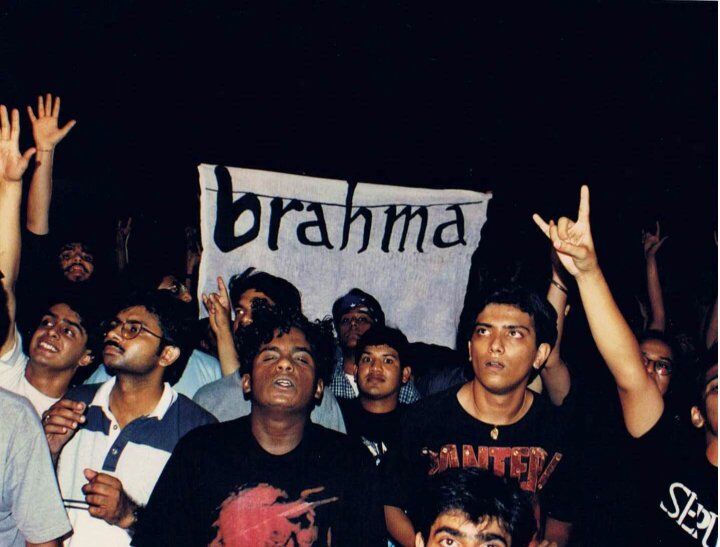

Among bands like Pentagram, Agnee, Parikrama and more performing, metal band Brahma was active in the Nineties and 2000s, fronted by Devraj Sanyal. Today, he’s the chairman and CEO – India & South Asia of Universal Music Group and runs a wellness label called Vedam Records, but there’s plenty of footage of him and his bandmates at I-Rock editions, alongside favorites like Millennium, Parikrama and Pentagram.

Sanyal recalls performing at I-Rock and Great Indian Rock Festival (GIR), Rock ‘N India and several other concerts across the country, ranging from clubs to bigger stages. “Playing these crowds was the most fun I’ve ever had being on the other side of the music business, and it was always a thunderous, heart-pounding rush,” he says. Bands couldn’t have had it better, even if playing conditions were less optimal for them compared to the international headliners who were walking in with tech riders and demands. He recalls seeing everyone from Deep Purple to Bon Jovi to the Rolling Stones to Iron Maiden and the Scorpions. “As fans, we felt a cacophony of pure energy, and for us diehards, it was always a maelstrom of sound and sweat. And we left feeling richer for having experienced the greats,” Sanyal says.

Sampat, for his part, recounts the Rolling Stones concert at Mumbai’s Brabourne Stadium in 2003 as “badly done.” He says, “The concert was done at a venue near the road, so you could hear buses and taxis honking. They had to turn up the volume of the stage sound to counter that.” What was rewarding, however, was the chance to meet Mick Jagger at the Cricket Club of India (CCI), where Sampat was a member. That kind of chance meeting and willingness to spend time with fans is now lost, Sampat laments. “Today, you’re nothing more than a number. You’re taken for granted. It’s also become more of a social event,” he adds.

By the Nineties, the Great Indian Rock festival became a traveling series across the country. On the other end of the spectrum were beach raves in Goa that birthed the Goa Trance movement and made the territory inextricably linked to electronic music. Where crowds flow, capital usually follows. And it could be argued that that’s where the corporatization of music festivals began with companies like Percept launching their own international-focused EDM festival Sunburn in 2007. Back then, it was an attempt to consolidate the market and give a home for electronic music fans around the country. Promoters like Submerge had already been in action since 2003, fostering electronic music as an underground movement that was about to blow up. Submerge co-founder Nikhil Chinapa, who was festival director at Sunburn, recalls, “The early editions were a lot more about music, because they happened in the absence of Instagram-led FOMO [fear of missing out] and fans came for one of two reasons — either they knew the artists, or they knew that being part of a festival experience was something unique and not seen before in India. They had seen festivals online across the world, and they wanted to participate in the birth of this new form of cultural and community togetherness.”

As stage production and lineups grew bigger to emulate EDM festivals overseas, promoters like Submerge and Percept got sponsorship backing in a big way, which shaped the way brands came into the music festival experience. Back then, it also helped that artists were willing to waive their fees so that they could come to India. “When I brought Above & Beyond to play at the first edition of Sunburn in India, they charged me no fee and only came for the price of their flights and hotels. They wanted to experience what India was like,” Chinapa says. Interestingly, Above & Beyond headlined the Mumbai edition of Sunburn between Dec. 19 to 21, 2025.

Chinapa moved on from Sunburn to become a key curator at festivals like Vh1 Supersonic and Satellite Beach Party and is now festival director at Arunachal Pradesh’s Euphony Voyage, taking place on Feb. 13 and 14, 2026 in Itanagar.

After the likes of Sunburn, Big Chill, NH7 Weekender and others slowly came up, the idea of a music festival had also changed massively from just seeing your favorite artists on stage to a lived experience that you could keep going back to. Social media, according to Chinapa, is a large driver of FOMO-anxious audiences. But there’s another reason, too, for musical festivals finding favor. “While experience is still important, people think or people find that culture and community and their tribe and being a part of that movement together is as important as experience,” he says.

It’s those intentions that set the tone for the music festivals that have come up around the country today. They were largely accessible in terms of location, offered exclusivity when it came to top-notch artists (who may or may not have returned to India in the decades since), and built a brand value that has turned into legacy. They also likely served as a compass or litmus test, becoming the events that experimented, failed and succeeded in their curation, organization and pricing so that future festivals would navigate with a little bit of knowledge of what has grown from a national music circuit to a concert economy.