Hello and welcome to another edition of the Weekly Vine. In this week’s edition, we look at the new French-Canadian alliance against imperialist America, explain why Trump is the most Left-leaning American president, explain the problem with the “2026 is the 2016” trend, and finally reveal why the pointy-haired boss will live on.

A Frenchman and a Canadian stand up to America

Every time I hear a Frenchman speak English, I am reminded of Steve Martin’s Jacques Clouseau from The Pink Panther remake, particularly the scene where he learns how to order a hamburger, which later leads to the hilarious airport scene in the movie.

I was briefly reminded of Clouseau while listening to Emmanuel Macron deliver a stinging rebuke to Donald Trump at the World Economic Forum in Davos, an event where rich people often rack up their carbon footprint while talking about how they can reduce the global carbon footprint.

But what was unique in this year’s address was Macron’s—and other leaders’—stinging rebukes of Trump. It marked a rare departure from Europe’s rather sanguine posture as Trump has repeatedly threatened a continent that appears to have lost its mojo. Once known for sailing the seas to sell opium and oppression, Europeans had become largely comfortable in the post–World War II rules-based international order, with America picking up the cheque. But all that has changed with the second coming of “Daddy” Trump, who has decided to talk tough to Europe (and Canada).

Macron—channelling his inner de Gaulle (or Napoleon)—said France and Europe must stand up to bullies. In a sharp reply, delivered while wearing tinted glasses, he said: “But we do prefer respect to bullies. We do prefer science to plotism, and we do prefer rule of law to brutality. You are welcome in Europe and you are more than welcome to France.”

(For those wondering what “plotism” is, it most probably refers to conspiracy-theory driven thinking.)

It would appear Macron is done playing nice, especially after Trump leaked his most recent direct messages on Truth Social. He wasn’t the only one pushing back. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen warned that any threat to Greenland would lead to a “united and proportional” reaction. Belgium’s Bart De Wever said his country would not be a miserable slave to Washington, while Sweden’s Ebba Busch urged Europe to “toughen up” and stop assuming US goodwill is a given.

But perhaps the strongest rebuke came from a country known for being too mild: Canada. Popular American culture loves to portray Canadians as overly apologetic and unfailingly polite, but that stereotype was nowhere to be found in Mark Carney’s speech, where yet another US ally made it clear they had had enough of being dismissed as the 51st state.

Carney who has enjoyed the Trump bump, the bump that LW leaders across the world over backlash to Trump’s policies, announced the “death” of the so-called rules-based international order.

Using Vaclav Havel’s greengrocer analogy from the essay The Power of the Powerless about how communism survived, Carney announced the death of the rules-based international order. Instead, he proposed that middle power nations to smell the coffee and said: “We are taking the sign out of the window. We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy, but we believe that from the fracture, we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just. This is the task of the middle powers, the countries that have the most to lose from a world of fortresses and most to gain from genuine cooperation.”

He added: “The powerful have their power. But we have something too – the capacity to stop pretending, to name reality, to build our strength at home and to act together. That is Canada’s path.”

All of which makes this a very interesting time to live in because who knew that that the first ones to stand up to American imperialism would be a Frenchman or a Canadian, a statement that sounds like it was borrowed from “walked into the bar” joke.

United Soviet States of America

Donald Trump is routinely described as a right-wing white supremacist nationalist. Much like the Holy Roman Empire, none of those labels are accurate. He is not right-wing, not particularly nationalist, and not driven by race in the way his critics imagine. Trump is transactional, self-interested, and ideologically promiscuous. And if ideology must be assigned, his governing instincts place him firmly on the Left.

The confusion stems from a poor understanding of what “Left” and “Right” actually mean. The terms originate from the French Revolution, where radicals seeking to overturn the system sat to the left and defenders of the existing order sat to the right. The Left was never about kindness or equality; it was about rupture, grievance, and moral certainty. By that definition, MAGA fits perfectly.

“Make America Great Again” is a revolutionary slogan. It assumes the system is irredeemably broken and must be torn down and rebuilt. Like all successful Left movements, MAGA runs on permanent grievance. Trump and his supporters are forever oppressed, cheated, and victimised by shadowy elites, even while holding enormous power. This sense of victimhood is not incidental; it is the moral engine of the movement.

In office, Trump governs using a familiar Left-authoritarian playbook. He weaponises law enforcement, morally delegitimises critics, and demands loyalty over competence. Opposition is treated not as dissent but as betrayal. Elites are not abolished but replaced. Old elites are evil until they submit; new elites are virtuous once they are loyal.

Economically, Trump embraces state coercion. He pressures corporations, intervenes in mergers, caps prices, deploys tariffs as punishment rather than policy, and uses public money to bend private enterprise to his will. This is not free-market conservatism. It is statist economics.

Geopolitically, Trump views the world not as sovereign states but as influence zones to be dominated. Expansionism, coercion, and family enrichment follow naturally.

Trump is not a right-wing anomaly. He is the logical endpoint of Leftist populism stripped of restraint. Orange is the new red.

Read: Why Trump is America’s most Left-leaning president

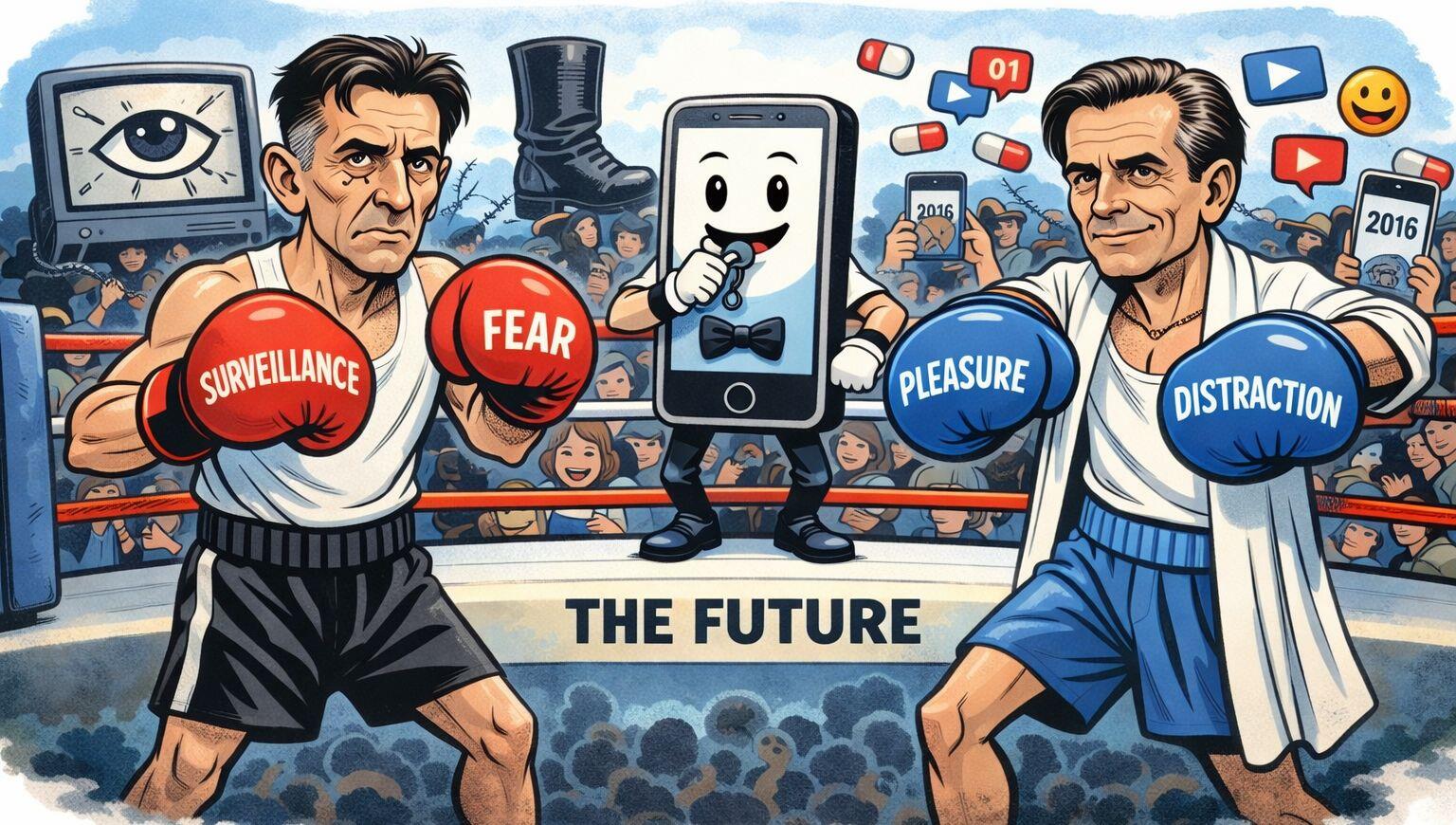

Huxley vs Orwell: The 2026 is the new 2016

In 1949, a year after Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell received a letter from his former French teacher at Eton: Aldous Huxley. Like all good teachers, Huxley first praised the novel and then ripped it apart, pointing out that Orwell had misdiagnosed the future of power. Huxley argued that Big Brother surveillance, the boots, batons, telescreens, and fear was too expensive and brittle and argued that the world would be more like his earlier novel Brave New World.

Critic and author Neil Postman summed it up best from his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, summed it up best which I am summarising below.

The two futures can co-exist and probably does. Orwell feared books would be banned. Huxley saw no reason because books would not be read. Orwell feared truth would be concealed, Huxley believed it would be drowned out by irrelevance. Orwell thought we would be captive, Huxley believed we would become trivial. In Orwell’s dystopia, we would be controlled by inflicting pain, but Huxley believed it would be controlled by inflicting pleasure.

I was reminded of that with the new “2026 is the new 2016” trend with people happily posting pictures from 2016 for the Deus Ex-Machina to train their algorithms and facial surveillance software.

What looks like nostalgia is really compliance dressed up as rebellion. There’s no need to harass users to share their data, they will do it themselves if you say it’s a trend. It was just as Huxley imagined culture dissolving: distraction masquerading as freedom, pleasure doing the work of power, and an audience so busy reliving itself that it has no idea its being mapped, predicted, and quietly managed.

Read: The problem with the “2026 is 2016” trend

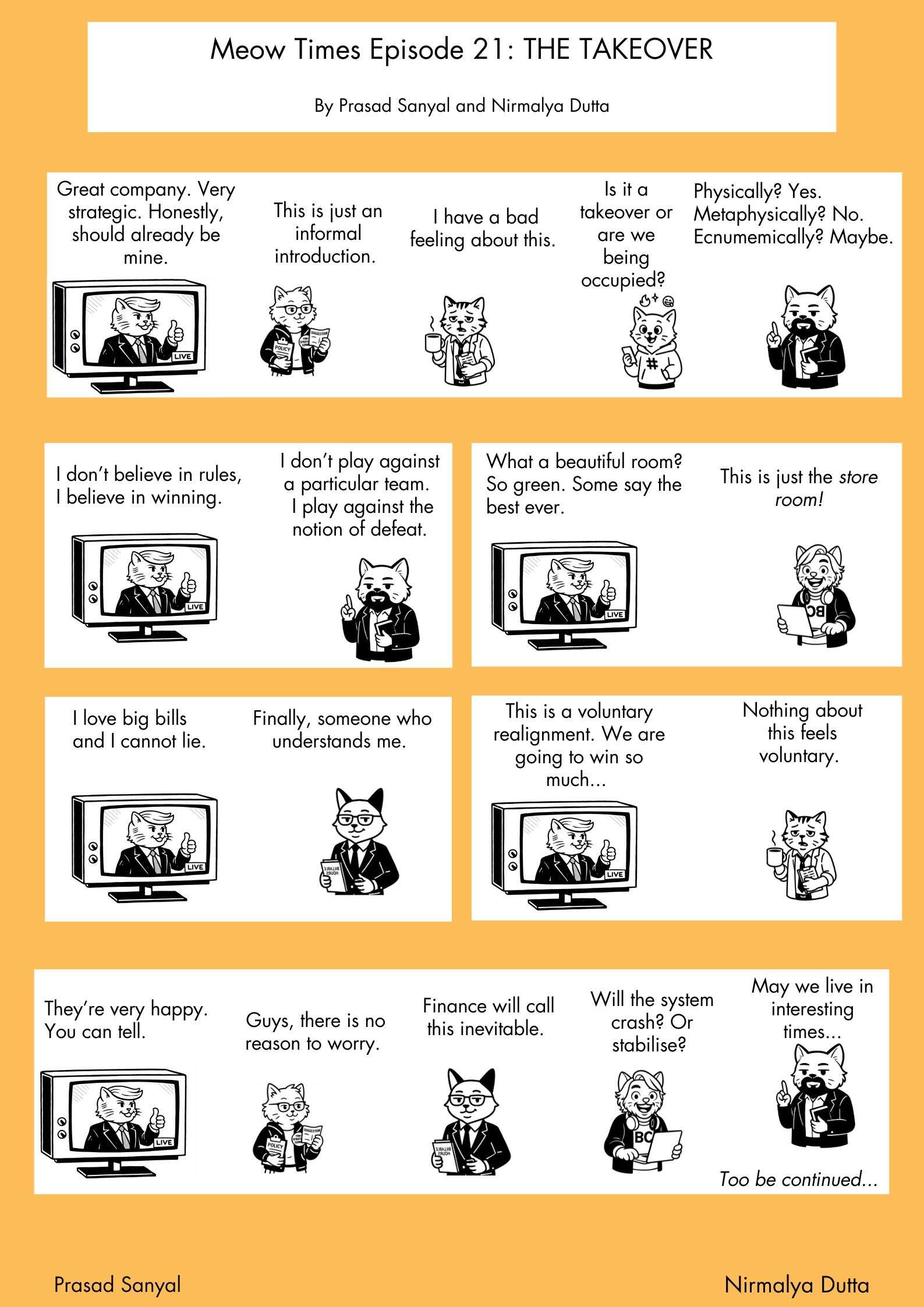

Postscript by Prasad Sanyal: The Pointy-Haired Boss Lives on

Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert, died on January 13, 2026.

It feels strangely fitting that the news arrived without spectacle, because Adams spent a lifetime observing how the most consequential things in organisations rarely happen with drama. They don’t explode. They linger. They continue. They refuse to end.

There is a sentence economists repeat with monk-like certainty: money you already spent should not influence your next decision. It is clean, rational, mathematically correct. And almost entirely useless in the real world.

Adams knew why.

Dilbert was never really about cubicles, bosses, or bad meetings. Those were props. What he was documenting—patiently, mercilessly—was the human inability to let go of the past once we have publicly committed to it. The comic strip worked not because it exaggerated corporate life, but because it barely had to. Organisations, like people, are not governed by logic as much as they are governed by memory.

Read: Scott Adams is gone. The pointy-haired boss lives on…

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE