India’s K-pop explosion shows no signs of slowing down. What probably began with a BTS, Blackpink or EXO track in a cybercafé has now evolved into a full-blown cultural remix, sweeping across dorm rooms, school corridors and midnight bus rides nationwide. Fans are swapping lyrics, staging campus flash mobs and dreaming of seeing their idols perform live on home turf.

In the 2025 Global Hallyu Survey (based on 2024 data), India recorded the third-highest affinity towards K-content globally at 84.5 percent, after the Philippines and Indonesia, according to the Financial Express. And at roughly 185 million users, India’s K‑pop streaming numbers are a beast in themselves. In fact, when Korean entertainment giant Hybe, the agency behind K-pop supergroup BTS, recently rolled out its Indian arm in Mumbai, they said India’s streaming market is the second‑largest in the world, and “the perfect market to implement our growth strategy,” especially given the “remarkable rise of K‑pop in India.” Not to be outdone, K-pop icon G‑Dragon’s agency Galaxy Corp. is reportedly scouting the subcontinent and plans to open an Indian branch by early next year.

The influence of K-pop has also trickled down into fashion, food, beauty, language and everyday culture. Korean restaurants, beauty aisles and language classes are booming, with Korean Culture Centre (KCC) registrations jumping from 814 in 2020 to 4,680 in 2021, while KCCI-supported school programs reported a rising trend from 1,535 enrolments in 2023 to 2,572 in 2024.

Yet, despite all this frenzy, the dream of a full-scale K-pop festival in India remains frustratingly out of reach. Physical festivals, the beating heart of the K-pop experience, keep getting stuck in a stuttering loop. Online, the craze is deafening, but live K-pop events on Indian ground remain a shaky, under‑cooked affair. It’s a crazy catch-22: everyone’s hyped, and the hype is off the charts, but the practical side just can’t keep up.

The Infrastructural Choke Point

India’s live‑event scene is unarguably on the rise — estimates based on a joint report by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) and Ernst & Young (EY) say it’s expected to steadily grow from ₹88 billion in 2023 to a whopping ₹143 billion by 2026. It’s an exciting time for the concert economy in theory, but on ground, the country’s sheer scale and diversity can turn any big‑ticket festival into a Herculean puzzle. Outside the usual suspects — Delhi, Mumbai, and Bangalore — there are barely any venues that can handle the volume of sound, lighting, security, and crowd‑control gear that a world-class concert demands.

Nikita Engheepi, a pioneer of India’s K-pop concert scene and Co-Founder of Pink Box Entertainment (a premier K-pop event agency) and Namaste Hallyu (Korean media website), says, “India has pulled off big concerts, but we don’t yet have enough venues for a country this massive. With faster permissions and more mid‑to‑large spaces, K-pop events could scale instantly. The demand is already huge, but the ecosystem just needs to catch up.”

The ground reality of staging a K-pop show is that the whole production often has to be airlifted in, which spikes costs and makes organisers think twice. Jason Manners, CEO of Rockski and Festival Promoter of Shillong’s Cherry Blossom Festival, highlights, “Logistical and financial constraints are killing [these experiences]. Flying in international artists is expensive, and sponsors are hard to come by. India’s festival infrastructure isn’t exactly top-notch either.” The result is that fans are left scrolling through livestreams while the live experience remains just beyond our grasp.

The market is still finding its feet. Most big domestic events happen in open-air spaces that aren’t actually designed for concerts and end up running short on creature comforts. Take the case of the Bryan Adams gig last year in Mumbai, where just three bathrooms were available to accommodate a thousand attendees, resulting in a spectacular screw-up. A bigger challenge is technical flexibility: adjustable decks, elaborate rigging, and premium audiovisual setups aren’t always easily available, so delivering the high-octane spectacle K-pop fans expect is a logistical nightmare. Traffic jams, unsafe parking spots, and insufficient safety precautions make the situation more difficult. Popular Indian singer and actor Diljit Dosanjh even called out some of these inadequacies during his December 2024 “Dil-Luminati” tour, saying there isn’t enough infrastructure to support live shows in India and urging authorities to act. His remarks definitely stirred the pot — some called him out for being a bit too harsh, given the success of Coldplay’s 2025 gigs, while others agreed he had a valid point about the urgent need for better venues. Bottom line: when you’re booking a big, international concert or music festival, the whole setup has to meet global standards.

Sukanya Bandopadhyay, a longtime K-pop enthusiast, sums it up: “Korean entertainment companies work with a level of structure and predictability. They look for venues that can support heavy production, organizers who understand the pace of Korean concert routines, and a local ecosystem that can handle a crowd without losing control. India has the enthusiasm, no doubt, but the infrastructure is still catching up.” She points out how events like the K-Town Festival made that painfully clear—long lines, patchy communication, delays, and a sense that organizers underestimated what the audience needed. “For fans who’ve seen how Korean concerts run, even through videos, the difference was obvious,” she states. “And for Korean agencies watching from afar, these lapses don’t inspire confidence.” The broader issue is that India still lacks enough mid-sized, technically consistent venues. A K-pop show isn’t just a musical performance; it’s a tightly choreographed production with lighting cues, live screens, sound precision, and safety checks. Without that baseline, it becomes hard for international acts to commit and even harder for festivals to grow into something stable, she adds.

The Economic Equation

The economics of pulling off a K-pop show in India are a tough equation. K-pop has established itself as a global brand with a premium price tag, and that premium shows up the moment you start ticketing a concert. Bringing A-listers to the country means shelling out massive performance fees, flying in an entourage of dozens, and hiring state-of-the-art audiovisual setups that most Indian venues simply don’t have. Against a still-developing live event market, those costs push ticket prices into a range that easily outprices a big chunk of the young, passionate fanbase that fuels the hype.

The primary hurdle, whispered in back-room meetings, is plain old financial viability. Even a single established act can feel like an astronomical undertaking: artist fees that sit firmly in the big-league bracket, complex logistics for travel and security, and technical riders that demand gear you can’t just rent from the local shop.

“Too often, ticket prices here make promises the event can’t keep,” Bandopadhyay notes. “Fans are willing to spend, but not to be shortchanged. When organisers charge global rates and deliver shaky execution, the devotion they rely on starts to feel exploited rather than celebrated.” The result is a tightrope walk between affordability and breaking even, and, more often than not, the rope snaps before the show even starts.

Production costs pile up on top of the artist fees, which pushes the budget north of what a typical Indian festival spends. Venue scarcity doesn’t help either: India has few globally compliant arenas, so organizers end up converting stadiums or hiring makeshift spaces, then pouring money into extra infrastructure—public transport links, parking, toilets, waste management— just to make the venue work. Plus, licensing is a bureaucratic maze, with over ten separate permissions required, from venue booking to security clearances. The whole process tends to be lengthy, unpredictable, and, at times, opaque, and an added 18 percent GST (Goods and Services Tax) squeezes margins even further.

As Ashish Hemrajani, Co-founder & CEO of BookMyShow, told The Economic Times: We need a clear policy at the national and state level that makes it easier to host events, keeps people safe, maintains decent sanitation, and gets the logistics sorted. Audience spending power is another weak link. While India boasts a massive young population that lives for K-pop, the average fan’s disposable income is modest compared to fans in Japan, South Korea or even Southeast Asia. Ticket prices for a K-pop festival can start at ₹2,499 (as seen with the K-Wave Festival 2024 featuring Hyolyn and Suho of EXO) and keep spiking upwards, shutting out many would-be concertgoers. According to a Reddit user, going to a concert in India has become a status flex — tickets are sky-high because venues are scarce and the rich can overspend without hesitation. The top 0.1 percent hold about 40 percent of the wealth, so expensive tickets barely make a dent for them. That elite spending sets the bar, pushing K-pop concert and festival tickets far beyond what most fans can afford.

But there’s a bigger narrative here: the contrast highlights the evolving dynamics of K-pop fandom in India. As Engheepi puts into perspective, “When we started in 2015, the real challenge wasn’t logistics, it was proving that India even had a K-pop fandom and getting fans used to paid experiences like fan meets and hi-touch sessions. Our goal has always been to put Indian fans on the map and grow the market.”

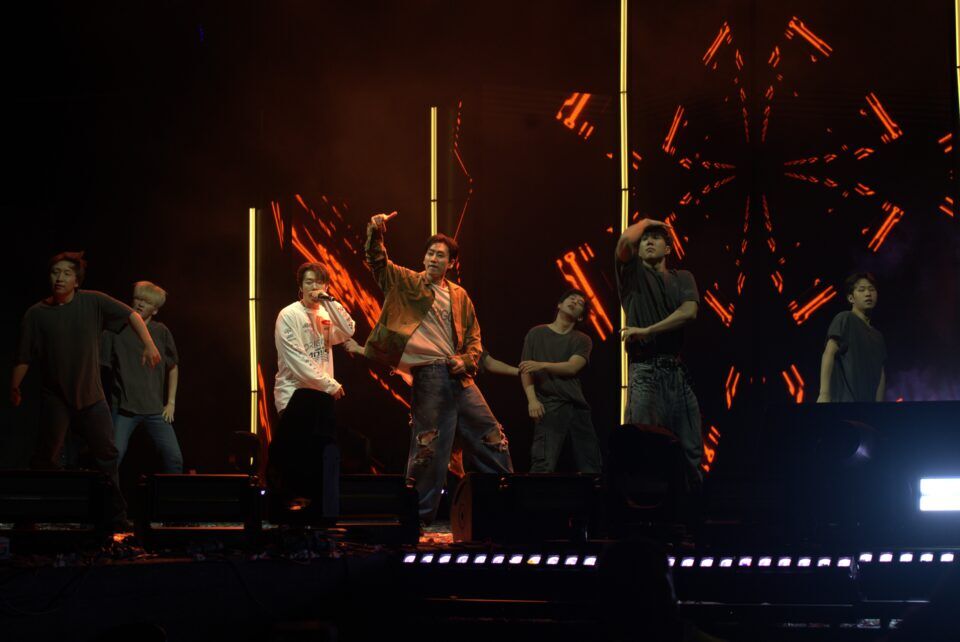

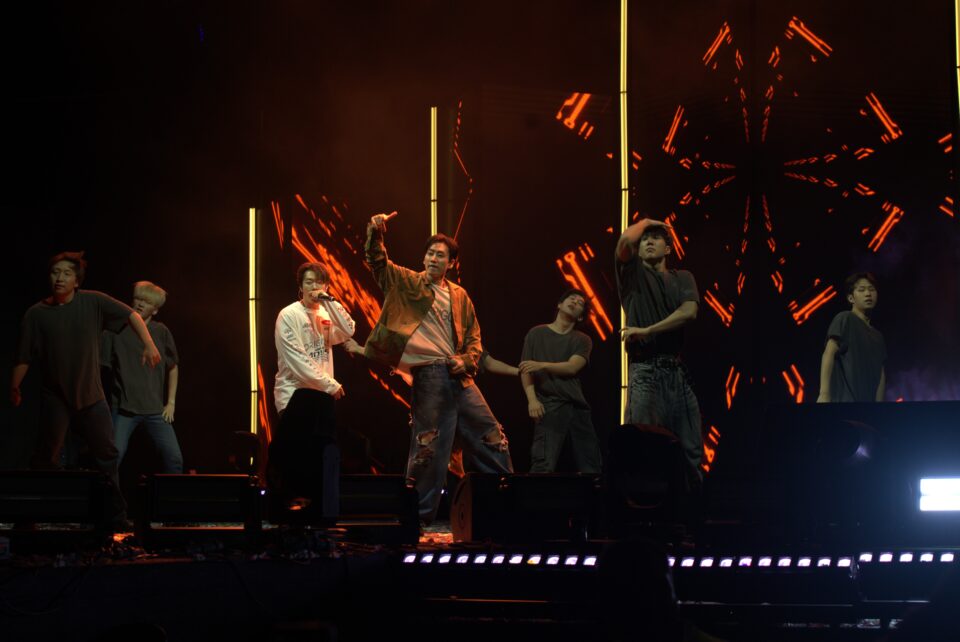

When you look at the actual shows that have happened, it’s a patchwork of trial runs. Jackson Wang (GOT7) performed at Lollapalooza Mumbai in 2023, but India wasn’t on his “Magic Man World Tour” at the time. KARD toured pre-2020, and Kim Woojin (ex-Stray Kids) played smaller venues. In late 2024, a slate of names—Suho, Hyolyn, Chen and Xiumin of EXO, B.I, and Bambam of GOT7—played at the K-Wave and K-Town festivals. This year, Taemin (of Shinee), Super Junior-D&E, Yedam, Jey, and OneWe headlined K-Town 3.0, and Everglow was one of the headline acts for the Orchid Music Festival in Sikkim. These multi-artist festivals are a safer bet, a way to spread the risk while still feeding the frenzy. Yet the underlying pattern remains: fans can’t afford the high prices, so big artists often stay away, and without regular big-ticket shows, the market never builds the concert culture that could justify those prices. And until that loop breaks, K-pop concerts in India will stay rare.

An Indian event organizer, who requested anonymity to protect his privacy, reiterates, “Everyone talks about demand, but nobody mentions that the real barrier is affordability. We’d love to keep tickets at ₹2k or maybe even less, but with the exchange rate and the artists’ fees, we’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. At the end of the day, it’s a vicious cycle: high costs mean high ticket prices, and low attendance from the youth who drive the K-pop craze. Until the cost structure changes, these festivals will stay niche, no matter how loud the fans may scream.”

A Narrative of Unmet Demand

The result? A passionate community that’s forced to live the love second-hand. Instead of waiting for a marquee name to show up, they’ve taken matters into their own hands, setting up meet‑ups, fan projects, and streaming bashes that turn the digital space into a lively subculture of its own to keep the hype alive. As Tanvi Lahiri, a member of a Kolkata-based K-pop fan club, says, “Honestly, we can’t wait for a big city K-pop festival — so we just create our own mini-fest every month. We rent a tiny community hall, set up LED lights, and stream the latest MVs together, celebrating our biases’ birthdays, and engaging in fun karaoke while we snack on our favorite ramen and kimbap. It’s our way of living our K-pop dreams without breaking the bank.”

Elaborating on this narrative that speaks to the unmet demands of K-pop fans in India, Jason Manners points out that “language barrier, low buying power, and lack of emotional connection with the content” are some of the main reasons behind the struggle. He asserts, “Indian fans aren’t used to the fandom marketing strategies that work in other countries, and K-pop companies don’t have a strong presence here.” This one-sentence rundown sums up a whole lot of friction: language, money, and a feeling that the music is still just out of reach for most fans. There’s an eager audience, but the industry hasn’t quite figured out how to tap into this market effectively just yet.

“To make K-pop festivals work, we need to get creative.” Manners theorizes and adds that collaborating with local artists, offering affordable tickets, and providing English subtitles or dubbing are key. “Most importantly, K-pop companies need to establish a presence in India and engage with fans.” In other words, the formula is part local flavor, part smart pricing, and a lot of genuine fan interaction. Having worked with artists like Kim Woojin, Alexa, Pixy, Lucas, and Everglow in cities ranging from Shillong to Bangkok, Sikkim, Delhi and Mizoram, Manners states, “I’ve seen firsthand what works and what doesn’t,” stressing that smaller K-pop companies are more likely to succeed here because “they’re willing to adapt and lower prices. Online events or streaming could also help reach a broader audience.”

It makes sense that the struggle is a clash between a global cultural phenomenon and the gritty realities of Indian logistics, economics, and bureaucracy, causing the dream of a massive K-pop festival in India to remain a far-fetched one for millions of fans. At the same time, things are definitely shifting, with more and more K-pop idols and their agencies showing interest in India as a potential stop for performance and marketing. “Now, the landscape is unrecognisable,” admits Engheepi. “Everyone can see K-pop’s impact here, and watching Indian fans finally get the recognition they deserve has been incredibly fulfilling.”

The momentum is building with Jung Kook’s (of BTS) highly anticipated exhibition, Golden: The Moments, finally arriving in India — a clear signal that the exhibition is a trial run for larger events. Hybe’s statement underscores the strategic angle: “Our goal is to build meaningful cultural bridges, connecting our global artists with Indian fans, where the voices of India become global stories.”

For now, however, until the big stage arrives, the fans are keeping the party alive in community halls, Discord channels, and cramped living rooms – proof that when the big stage is out of reach, the subculture simply builds its own.