If you’re on Marine Drive in Mumbai, you most certainly have seen Pizza by the Bay, the Italian restaurant on the ground floor of Soona Mahal, one of the most striking Art Deco buildings on the bustling seaface. The streamlined building, built in 1937, features cantilevered balconies, vertical accents topped with stepped ziggurat motifs, and a rooftop turret.

The Queen’s Necklace on Marine Drive houses beautiful examples of this architectural style that took root a century ago, marked by geometric patterns, porthole windows, nautical motifs and the iconic Deco signage. In fact, Mumbai has the second largest collection of Art Deco edifices across the world, second only to Miami Beach.

Western India House, Fort

| Photo Credit:

Art Deco Mumbai Trust

The centenary of the movement in 2025 calls for celebration — and quiet reflection. One hundred years ago, on the banks of the Seine in France, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, a landmark exhibition that ran for seven months in 1925, marked the birth of Art Deco, a design language that departed from the ostentation of Art Nouveau, the excesses of Victorian, and classical architecture. Emerging alongside the functional minimalism of German Bauhaus and the modernity of materials like glass, concrete, and steel, Art Deco embraced a bold aesthetic, featuring motifs such as frozen fountains, ziggurats (rectangular stepped tower), sunbursts, speed lines, and elements from Egyptian and Aztec cultures.

In the years bookended by the two World Wars, migration and travel brought it to India. Affluent Indians, introduced to the aesthetic in Europe, asked architects back home to incorporate Deco elements into their new construction. Mumbai, Chennai, New Delhi, and Kolkata saw its strongest architectural expressions, while cities such as Pune, Hyderabad, and the Chettinad region developed more local interpretations.

Bank of Maharashtra

| Photo Credit:

Art Deco Mumbai Trust

Today, not all of it has survived, and there is an urgent need for documentation and conservation. But, on the brighter side, contemporary movements in textile, typography and design have been incorporating Art Deco motifs into their visual vocabulary. But more on that later.

Documenting Deco, one city at a time

Atul Kumar, founder-trustee of the Art Deco Mumbai Trust, and his team have documented Mumbai’s Art Deco heritage, identifying 1,324 buildings since 2017. From residential multi-storeys with geometric ventilators and chevron patterns to government edifices and cinemas, the Trust’s interactive map shows those interested where they are located.

In its sister city, Pune, the buildings have a strong vernacular influence. “We see the incorporation of mythology, lotus motifs and the Devanagari script,” says Kumar. Sugandhi Building, a family owned three-storeyed residential structure in Budhwar Peth, is a favourite for its evocative lotus imagery, vibrant palette, and trademark Deco features such as circular portholes and a mandap-like deck — its moniker derived from a family that specialised in perfumery and fragrances, living in Pune for over 200 years.

Lotus imagery at Sugandhi Building

| Photo Credit:

Abhishek Gijare | Art Deco Mumbai Trust

Hari Krupa or Mehendale Building, a two-storeyed mixed-use building with shops on the ground level, in Sadashiv Peth, is a prime example of how local craftsmen wove Art Deco influences into the local fabric, with religious iconography such as swastiks and omkars, sunbursts and chevrons. “There is a unique melding of western and Indian styles — the designs are more intricate, and not as stylised as the Art Deco form,” he shares.

Hari Krupa, the family house of the Mehendales

| Photo Credit:

Abhishek Gijare | Art Deco Mumbai Trust

As most of the 90 residential buildings in Pune now house families and commercial enterprises, documentation has been tough. “We are focusing on outreach and sensitisation. Urban pressures [such as rapid plot development] are similar across cities, and there is no incentive to preserve or restore these homes. But the families we visited are keen to learn more about their heritage,” adds Kumar.

This sentiment is echoed by Adhiraj Bose, who has been documenting Kolkata’s Art Deco heritage since 2017. The city has one of India’s earliest high-rise Deco buildings — the Tower House, built in 1928 — and a residential home, Jahaj Bari on Elgin Street, shaped like a ship, reflecting the city’s love for maritime imagery.

Hindu Mutual Building on Central Avenue

| Photo Credit:

Adhiraj Bose

Bose leads heritage walks, photographing hundreds of residences in Lake Town and various government buildings. “Demolition and redevelopment are more popular and economically viable than restoration. The Red Bari café opposite the Kalighat temple, Roastery Coffee House in Gariahat, with its deep ochre and white walls, and the Broadway Hotel are examples of ‘repurpose and restore’ initiatives,” explains Bose, who is currently striving to preserve the vestiges of single family Deco homes in his neighbourhood, Lake Town.

Just a fashion statement

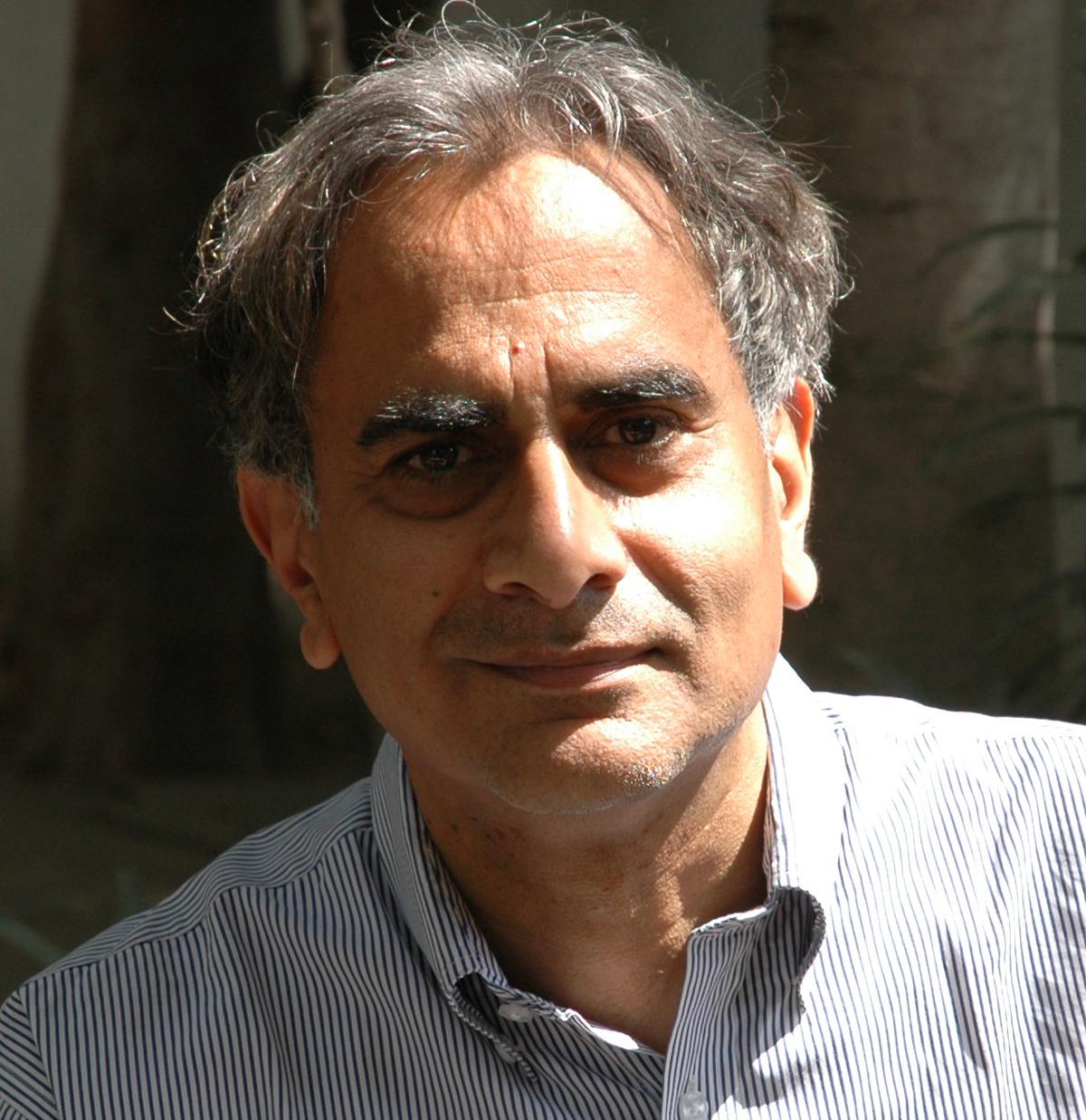

“I’ve never looked at Art Deco seriously,” says New Delhi-based architect Gautam Bhatia. “I feel it is not an architectural style; it is more a decorative and ornamental one. It was a temporary, transitory phase going from the classicism of the late 19th and early 20th century into modernism. In India, what you see is a sort of exaggerated opulence in buildings — fancy lighting, stylised lettering, metallic ornamentation, all of which is two dimensional. It doesn’t have the appeal of any kind of three dimensional spatial quality. It is what people would construe as a kind of fashion statement in architecture. You didn’t need to worry too much about what is inside. In fact, in a lot of places, the spatial quality was completely neglected. Which is why Art Deco was perfect for cinemas. It drew people in from the outside into complete darkness. The only thing that is attractive about Art Deco is that it made people look at architecture. It is like a painting on a street. You can’t ignore it. It made people look up and stare — whether it was Regal Cinema or some apartment block in South Bombay.”

As told to Surya Praphulla Kumar

Gautam Bhatia

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Inclusion of local sensibilities

Meanwhile, in the capital, where mostly Mughal and British Colonial styles dominate, Art Deco still manages to shine. Architect Geetanjali Sayal, founder of Deco in Delhi, a narrative website and Instagram page, began documenting the style around 2020 with researcher Prashansa Sachdeva. With 22 “pure deco” buildings, and a mix of four hybrid and 13 influenced structures, “we took a cartographical approach, starting with hand-drawn maps of Chandni Chowk and Daryaganj, archiving individual houses and small neighbourhoods”, says Sayal. “The focus wasn’t just on ornamentation, but design features like fireplaces, staircase structures, and flooring.”

22 Pusa Road, Karol Bagh (1940s)

| Photo Credit:

Lumilanous

Smaller cities saw the rise of Indo-Deco, a blend of modern construction and local sensibilities. Heritage architecture enthusiast Smita Babar highlights Chettinad’s façades with its egg-lime plaster and stencil drawings, tucked away in the bylanes of Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu. The mansions reflect a desire to straddle two worlds at the turn of the 20th century, when affluent Chettiar bankers built homes with traditional courtyards framed by imported glass, marble, and teak, adopting Art Deco elements for their façades.

“Bas-relief figures of goddess Lakshmi sit alongside running bands, concrete and metal grills, and chevrons, highlighting how Art Deco was adapted,” she explains. Abandoned by families who migrated to cities, many homes (estimated to be between 10,000 and 15,000, according to UNESCO) are maintained by caretakers or agents. “Any restoration or conservation will require a material-based approach, picking singular elements for restoration.”

‘Bas-relief figures of goddess Lakshmi sit alongside running bands’

| Photo Credit:

Smita Babar

Art Deco detailing on a Chettinad mansion

| Photo Credit:

Smita Babar

And one of the people stepping up to help is New Delhi-based architect Aishwarya Tipnis, who has developed a material toolkit — a free, research-based, online resource — to aid practitioners with the restoration process as well as directions on where to find the materials and skills. “A homeowner on Pusa Road in Delhi wanted to preserve their home and used it for terrazzo [material made with marble chips embedded in a cement or epoxy] conservation,” says Sayal, while Tipnis, whose goal is to aid informed renovation and restoration, adds, “We have to train professionals to embrace change in ways that are aesthetically, economically, and environmentally appropriate for the future.”

Aishwarya Tipnis

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

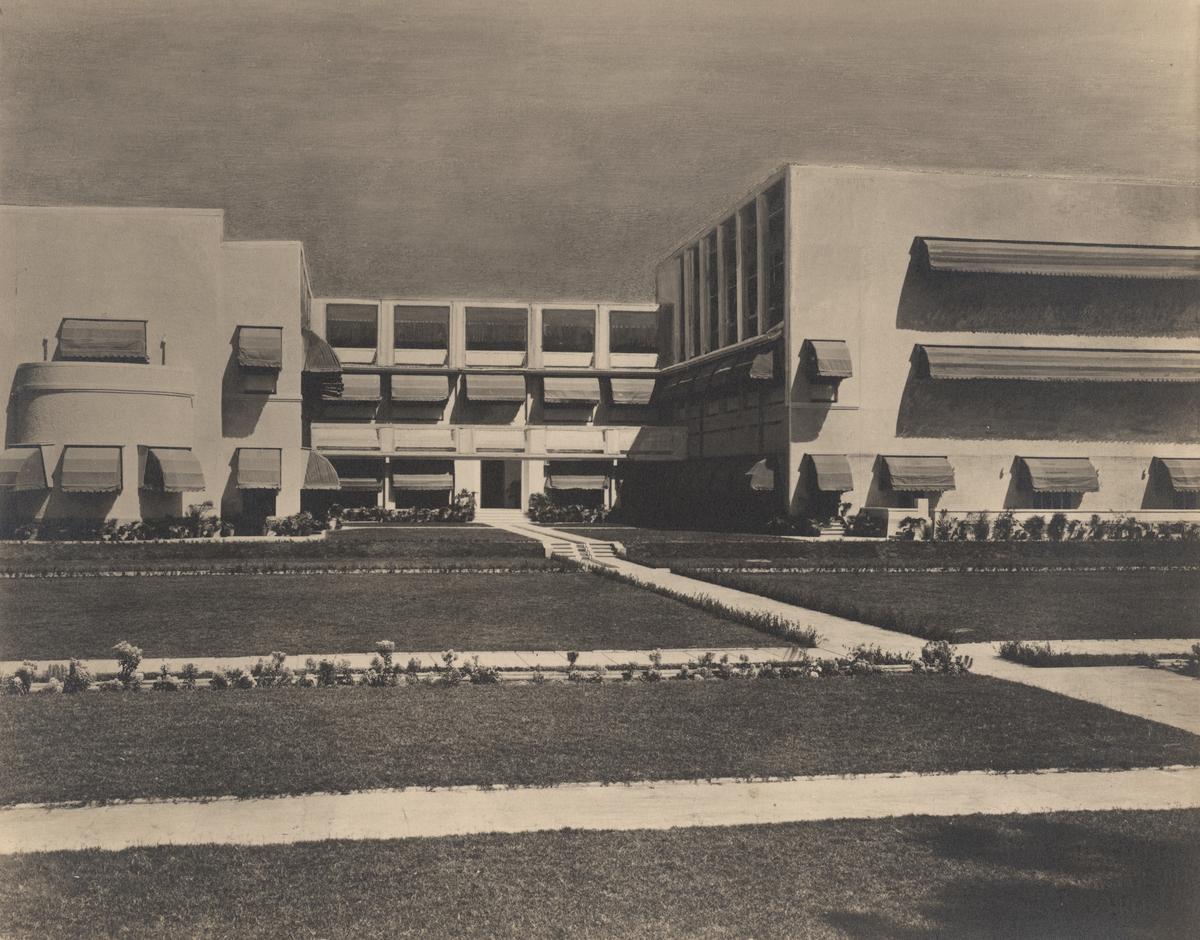

“It is good to see a new appreciation of spaces such as Manik Bagh as early expressions of distinctly Indian modernism, going beyond the overly simplified view that they were simply copies of what was trendy in the West. The collective vision of Maharaja Yeshwantrao Holkar II of Indore and architect Ekhart Muthesius of Berlin, Manik Bagh brought modernist design principles into an Indian context and began to shape the early thinking around Indian Modernism and Deco.”Yeshwant Rao HolkarHotelier and heritage conservationist

Yeshwant Rao Holkar

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Manik Bagh palace

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Letterforms meet legacy

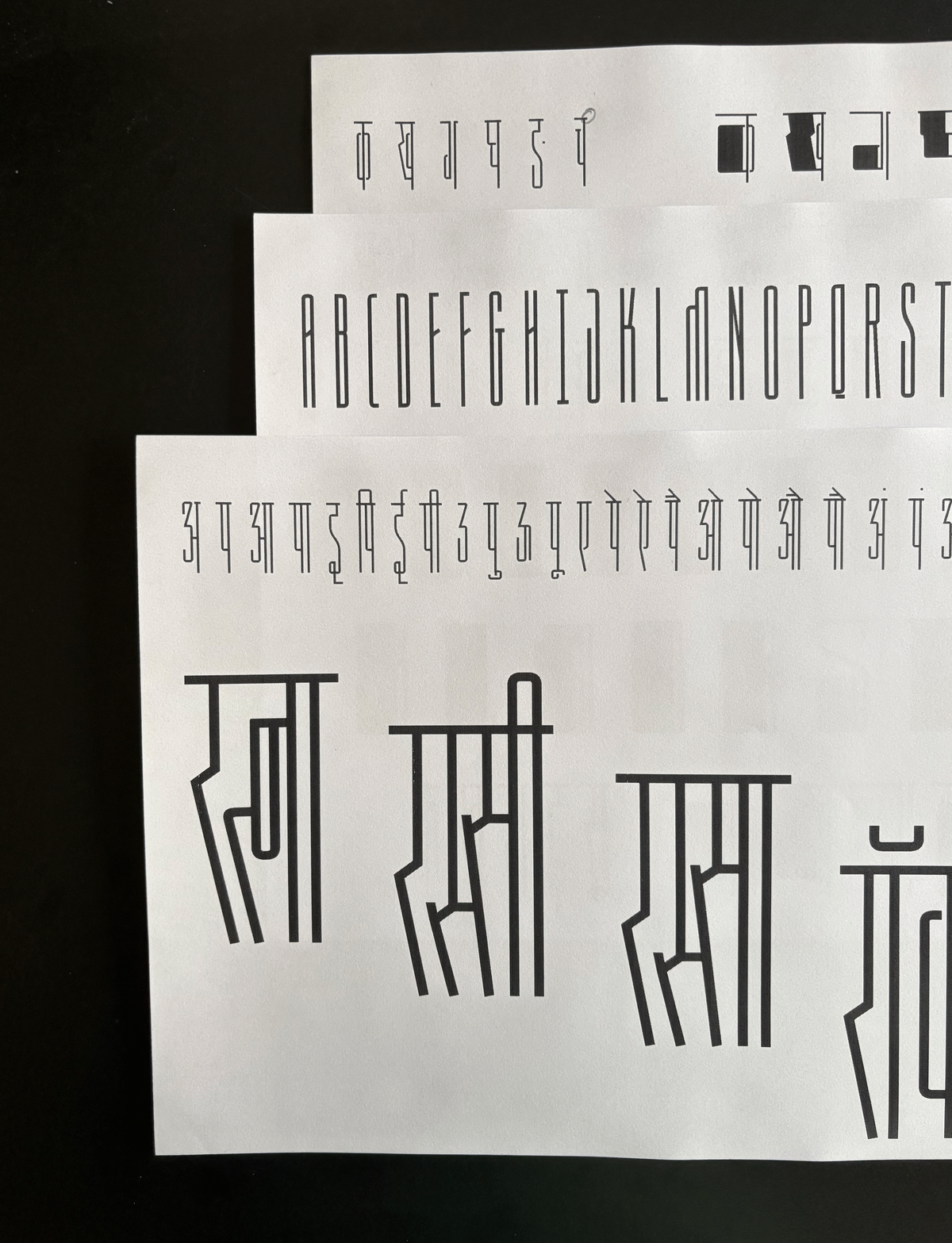

Art Deco has shaped not just Mumbai’s shimmering skyline; its visual grammar has also permeated the city’s typography. Tanya George, a Mumbai-based custom type designer, has been fascinated by its fonts. “I started noticing letterforms on buildings — printed, flex, and with adaptations of Indian scripts. Art Deco’s design captured the spirit of looking forward, so even their letterforms have longevity,” she explains.

George created Dekko during the pandemic (2020-21), a Deco-inspired typeface featuring tall figures, narrow fonts, and exaggerated waistlines, as seen in Devanagari and Latin scripts. “The project started with studying the letter forms, and the lockdown gave me more time to flesh out the design. Versions of the fonts have been used for identity across projects,” she says.

Dekko prints

| Photo Credit:

Tanya George

Sketches helped with the genesis of the English font, and the Devanagiri script followed suit. In her project with the Art Deco Mumbai Trust, she recreated the sign for Empress Court, an Art Deco building constructed in 1936, using archival photographs and modern materials such as stainless steel and polyurethane.

Empress Court

| Photo Credit:

Aashim Tyagi

Behind the sparkle

In May 2024, a vintage suite of Art Deco Platinum Jewellery was the highlight of online auction house AstaGuru’s ‘Jewellery, Silver and Timepieces’. Comprising a necklace, bracelet, ear clips, and a ring, the set sold for ₹1,86,91,200. “Globally, vintage and period-specific pieces are increasingly seen as style statements,” says Mumbai-based jewellery expert Jay Sagar. “Contemporary designers are drawing heavily from classic Art Deco motifs to create modern pieces that pay homage to the originals.”

A diamond and emerald Art Deco necklace

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For instance, jewellery designer Hanut Singh, whose pieces have been showcased by celebrities across the globe, offers a modern take on Art Deco, experimenting with rock quartz in jewels, or the crescent moon shape paired with the linearity in pavè diamonds, offering a glimpse into the glamour of the era.

Hanut Singh’s Art Deco inspired jewellery

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Hanut Singh

Art Deco has also inspired restaurant interiors. “The Bombay Canteen features vintage-inspired furnishing, terrazzo flooring, and intricate detailing,” says Sameer Seth, founder and CEO of Hunger Inc. Hospitality, adding that their Art Deco Cocktail Book features cocktails named after landmarks such as Liberty Cinema, Soona Mahal, and Sea Green Hotel. At the Bombay Sweet Shop’s Byculla store, the interiors feature curved glass displays and hand-blown glass lights, reminiscent of Mumbai’s iconic cinemas. And the signages of both “have typefaces that are bold, streamlined, and with geometric forms”, says Seth.

The Bombay Canteen

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Hunger Inc.

Bombay Sweet Shop’s Art Deco inspired font

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Hunger Inc.

The Bombay Canteen’s Art Deco Cocktail Book

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Hunger Inc.

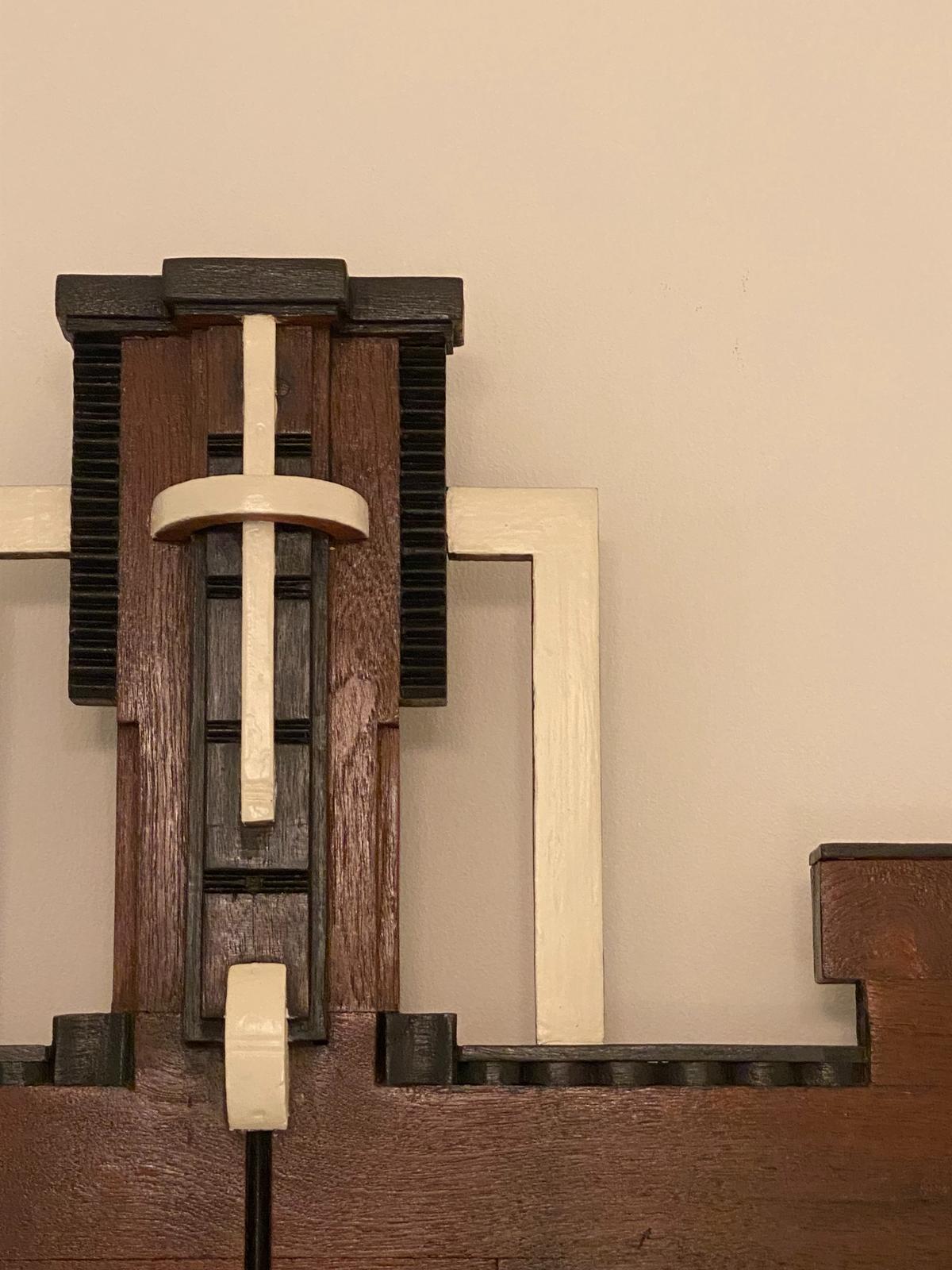

According to designer and restorer Kunal Shah, Art Deco’s timeless quality endears it to today’s designers. “There’s interest in objects like home décor, jewellery, rugs, saris, sunglasses, and shoes,” says Shah, who in 2022, curated a paean to Mumbai’s Deco movement with architectural photographs, art, collectibles, fashion, furniture, and typography at Gallery 47-A in Khotachiwadi. Juxtaposing Deco’s standout features against the current city design aesthetic, he says, “Art Deco sits uncomfortably with current aesthetic choices since today’s interior design style is aspirational, while [the former] was restrained and self-assured.”

Art Deco mirror details

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Shah

Porbandar’s gem

In the last wave of palace building, and in the early half of the 20th century, several significant Art Deco royal palaces were built — most famously Umaid Bhawan in Jodhpur, Manik Bagh in Indore, New Palace in Morvi, and Huzoor Palace in Porbandar. “Not many know about the last one. With its many wings and endless views of Porbandar’s French Riviera-like azure ocean, the Huzoor Palace is an architectural wonder,” says Deepthi Sasidharan, founder-director of Eka Archiving Services. “From its curving balconies and walls, ceramic and marble tiled geometric patterned walls and floors, to the pastel hued interiors and custom made thematic lights, fittings and carpets, it is an Art Deco masterclass.”

As told to Surya Praphulla Kumar

Huzoor Palace in Porbandar

| Photo Credit:

Deepthi Sasidharan

Woven into borders and pallas

Elements of Art Deco are, however, finding a new expression in Indian textiles and jewellery. In its Azalea collection (2024-25), Jaipur Rugs has reimagined iconic motifs with a bold black-and-gold palette in hand-knotted rugs. “The bold geometry, symmetry, and glamour have a quiet dialogue with India’s textile traditions,” says Rutvi Chaudhary, the brand’s director. “By reimagining these motifs, we celebrate this cross-cultural legacy and present it in a contemporary manner.”

Jaipur Rugs’ Art Deco design

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Jaipur Rugs

Raw Mango’s Art Deco sari collection creates shapes and forms characteristic of the movement, with streamlined woven ornamentation that is geometric and stylised, translating them into silk and brocade. Think arched scalloped pallas with gold zari and hand-embroidered borders of architectural motifs. “The collection began as a questioning of possibilities,” says Sanjay Garg, founder and textile designer, adding, “The challenge of any motif incorporation is to accurately capture the essence of textiles.” The research process spanned a minimum of two years or more in terms of design and sampling at the studio, whose flagship store in Chennai, Malligai, is housed in a stunning Art Deco two-storey house built in the 1960s on Cenotaph Road.

Raw Mango’s Art Deco sari collection

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Raw Mango

A century ago, India embraced a modern design language, imbuing it with its own cultural tapestry, creating Indo-Deco. Today, Indian practitioners of the style remain optimistic that this timeless design syntax will endure in form and function, supported by greater awareness, informed restoration, and detailed documentation.

“In the classroom, Art Deco is still not discussed in the same breath as other architectural styles because of the vast array of architectural wealth across the country. Our effort to document, study and preserve it, is to give the movement its due recognition,” Sayal concludes.

The freelance writer is based in Chennai.