For the fifth edition of the Dubai Pooram at the Etisalat Academy Ground in Dubai on December 2, 2024, four elephants were paraded in all their festive regalia. Gently swaying, shaking their heads, flapping their ears and swishing their tails, these jumbos were a sight to watch. One thing, though, these mechanical elephants were made by two Kerala-based companies.

Parading elephants in religious processions is a matter of pride for organisers and participants in Kerala. These parades are usually eventless, but of late, attacks by captive elephants, (especially in the first two months of 2025), have caused five deaths in Kerala. Despite protests, elephants are being used in such high stress events, which have noise of fireworks and loudspeakers, milling crowds of people and the mistreatment, which often trigger these attacks.

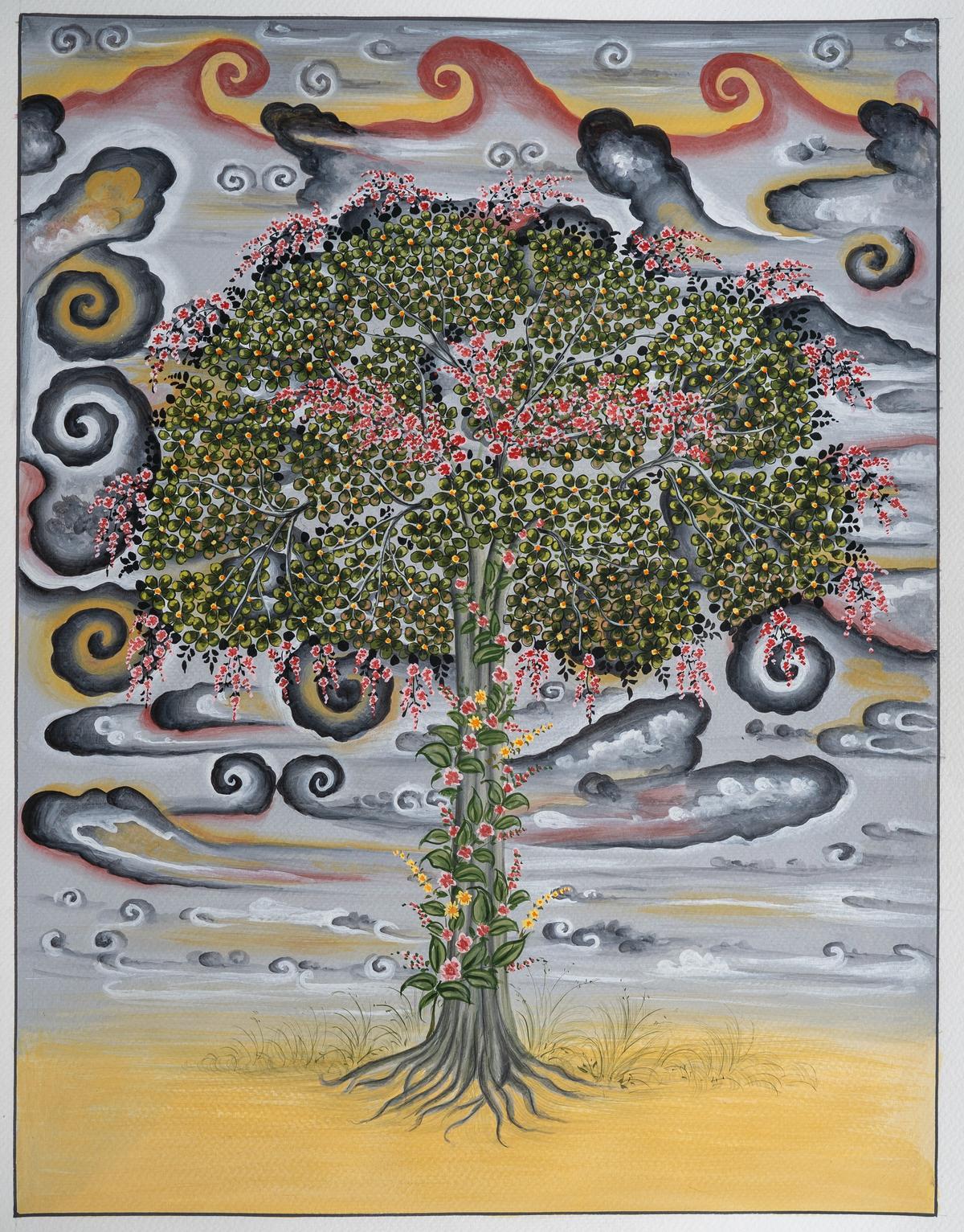

Workers engaged in making of mechanical elephants at Four He Arts Creations in Chalakudy.

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

A few temples in Kerala have voluntarily moved to mechanical elephants possibly because rules for parading an elephant in a temple have become strict as a result of the attacks.

Chalakudy-based Four He Arts Creations is one of the first companies in Kerala to make these mechanical elephants. The three elephants at the Dubai Pooram were made by them.

The four childhood friends — Prashant Prakasan, Santo Jose, Jinesh KM and Robin MR — made their first elephant, Kuttappayi, around 15 years ago. Built over six months, Kuttappayi was six-and-a-half feet tall. By the time Kuttappayi, with his bobbing head and swaying trunk, a swinging tail and flapping ears was ready, it was Santo’s sister’s wedding. Just for a lark, the friends decided to place Kuttappayi on a stage at the venue.

“He became the main attraction of the wedding! People then wanted to rent Kuttappayi for their functions, exhibitions, shop inaugurations etc in and around Chalakudy,” says Prashant. After that the four friends made motorised dinosaurs, The Jungle Book and The Hulk-themed sculptures, which they do even today.

Workers engaged in making of machanical elephants at Four He Arts Creations in Chalakudy.

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

Cut to the present. The rudimentary Kuttappayi is a thing of the past. The friends have graduated to making mechanical elephants to be paraded in temples, be put on show at resorts and other commercial places. So far they have made 46-odd elephants, not only for clients in India, but also Dubai, Singapore, Kenya and the United States. Four of their jumbos are part of a circus in Spain. Not only are these cruelty-free, they are low maintenance and can be rented out.

Donated by PETA

Prashant and his friends were recently in the news as People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), in association with sitarist Anoushka Shankar, donated the mechanical elephant Kombara Kannan made by Four He Arts Creations, to the Kombara Sreekrishna Swami temple near Irinjalakuda, in Thrissur.

Prasant Prakasan, Santo Jose, Jinesh KM and Robin MR with Kombara Kannan

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

So far they have made three elephants for PETA, which the organisation has donated to temples in Kerala.

From the road, the semi open-air production unit looks small. But a peek inside reveals a space large enough for a few ‘elephants’.

A ‘mould’ is being readied, while a technician works on the head of an elephant. Its trunk is a series of metal pieces being fine tuned to give it flexibility and a couple of other workers are painting details on a headless ‘elephant’. “There are no ready elephants right now. So far we have made elephants for six-odd temples in Kerala itself!” When they started it was just the four of them, now they have more than a dozen workers.

Apart from Four He Arts, Anamaker aka Sooraj Nambiatt, in North Paravur, 34 kilometres from Kochi, has also been making mechanical elephants. The day we meet, Sooraj is overseeing work on a 10 foot mechanical jumbo for a temple in Kottayam. Although he had been making sculptures of popular captive elephants since 2007, Sooraj’s foray into robotic jumbos is as recent as last year. He has made two elephants for PETA.

A worker puts together material that will go on to become a section of the head of a mechanical elephant

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

At Sooraj’s studio, the 10-footer headed for Kottayam, is getting ready.

The utsavam season is a hectic time for these elephant makers.

Robotic elephants

While Prashant and friends make mechanical elephants without venturing into likenesses of captive elephants, Sooraj, a post graduate in Fine Arts from RLV College, Tripunithura, makes elephants in the likeness of captive elephants if the customers so demand. “Customers ask for the face of say Pampady Rajan, elephants have distinct characteristics which people want for these. But of course you can’t call these elephant by the name of a living one. We improvise… so we have Robotic Raman,” says Sooraj.

In 2024, this elephant was the fourth mechanical elephant at the Dubai Pooram, and he was fondly called Dubai Raman. He made a mechanical replica of an elephant which recently died, Arjuna, for a temple in Mysuru.

Prashant says,“We make generic elephants because people are superstitious about making sculptures of things/people who are still living.”

Four He Arts Creations got its first order for the Dubai Pooram in 2018 thanks to a video of Kuttappayi the organisers saw online.

Although the Dubai Pooram order for three elephants was placed in 2018-19, the elephants were eventually ready in December 2020. The three elephants were paraded at the Pooram that year. The Dubai Pooram is the Dubai-version of the famed Thrissur Pooram.

“These electricity-powered elephants are made of fibre and are usually shipped internationally in containers. The elephant is ‘cut’ into four segments — the head, the body, front legs and hind legs. They are then assembled at the destination. For instance, we went to Dubai for the purpose, but could not go to either Tampa in the US or to Spain because we did not get our visas in time,” says Prashant. He did however go to Kenya to do a study on an African elephant for one they are making for a temple there.

Sooraj Nambiatt of Aanamaker with one of his elephant sculptures

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

While the eight foot elephants weigh under 300 kilograms, the 10-footers weigh under 500 kilograms. The prices for these range from ₹3.5 lakh to ₹5 lakh (at Four He Arts Creations and Anamaker). The rates are fixed depending on the movement of body parts — the head, the eyes, flapping of ears, the trunk (swaying/spraying water), tail, and limbs — these can be customised. A motorised elephant with all features is the most expensive. The detailing on the elephants, right down to the eyelashes and hair on the tail is stunning. These can bear the weight of up to four people sitting on them. These are mounted on wheelbases for ease of movement.

Kombara Kannan’s journey about to start from the workshop to Kombara Sreekrishna Swami temple

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

“We can even build one entirely of rubber, but that would cost around ₹7 lakh. It would feel very natural!” says Santo.

Making a jumbo

Made of fibre, mesh, rubber, foam and metal, it can take anywhere from a month to 45 days to build a motor-powered jumbo. Work first starts with making an elephant-shaped frame of steel square pipes and iron rods which is then covered with cement over which the fibre is poured and set. Once it sets, the mould is broken, the markings made on the body, smoothed and finished with the head being attached.

“Since these elephants were not manufactured here, we have had to experiment with materials and processes. Most of what we use is now locally sourced except the electrical/mechanical components which are bought online,” says Santo. Even now they continue to experiment with material. While the body is made of fibre, the ears are made of ‘rubber fabric’ that resembles a hide. While Santo and Jinesh work at Apollo Tyres, Chalakudy, Prashant and Robin work full time at Four He Arts Creations.

A mechanical elephant waiting for the finishing touches

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

Captive elephants in Kerala have a dedicated fan following. Elephant lovers or anapremis are a force to reckon with when it comes to the popularity of the elephants paraded in temples. Some of the popular ‘stars’ have run amok and attacked people during these festivals. Mechanical elephants are seen as diluting tradition; the makers have been getting a backlash. “We are not forcing temples to buy elephants from us. They are coming to us for these,” says Prashant. Interestingly Prashant and Sooraj have customers from outside Kerala, especially North India.

The Kombara temple has not used a live elephant for its temple procession since 2015 due to the cost and the suffering of captive elephants. Ravi Namboothiri, the temple president, says of accepting the mechanical elephant, “In honour of our decision to never hire or own an elephant for our rituals and festivals, we are absolutely thrilled to accept a mechanical elephant [from PETA]. All of God’s creations deserve love and respect!”

Sooraj says, “Maybe it is time we moved on to mechanical elephants. The treatment meted out to them is not the best. Elephants may have plenty of fans, but they are not treated like pets. They might be fed on time and bathed, and taken care of but are these elephants treated well? I have seen the dark side of this.” Once upon a time, he adds, there were 1,000-odd captive elephants in Kerala, many of whom were paraded in temples, he adds, “but today there are barely 200 or so left, and most of these are more than 50 years old. How long can [real] elephants be paraded anyway?”

Published – March 01, 2025 10:46 am IST