Buildings age the way cultures do: unevenly, politically, selectively. And cultures do not endure by clinging to form, but by carrying forward the spirit. Few practices make this distinction as tangible as conservation architecture. At its best, conservation is not about embalming buildings or sealing them off as relics. It is about keeping structures alive — socially, materially, and culturally — while acknowledging that time leaves marks, and that those marks matter.

In India, where cities grow as much by erasure as by expansion, conservation architecture sits at an uneasy crossroads. It is often reduced to sentiment, nostalgia, or elite indulgence. But speak to practitioners working in this field, and a different picture emerges: conservation as a way of thinking about continuity, repair, labour, and responsibility. Less about freezing history, more about negotiating with it.

Abha Narain Lambah, Mumbai

‘Buildings cannot survive as static objects’

Recent project: Completed the restoration of the long-shuttered Victoria Public Hall in Chennai, reimagining the 19th-century landmark as a public museum and cultural space. For her, such projects are not endpoints but catalysts. “What makes it meaningful,” she notes, “is when people begin to imagine what else could be restored.”

Some structures are celebrated, restored; others are left to crumble quietly. Lambah, who has worked across monumental heritage and dense urban precincts for over three decades, recalls that when she began her practice in the mid-1990s, conservation in India was narrowly focused on a small, official list of monuments protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act. Streets, markets, neighbourhoods, vernacular buildings — the everyday fabric of cities — simply did not count.

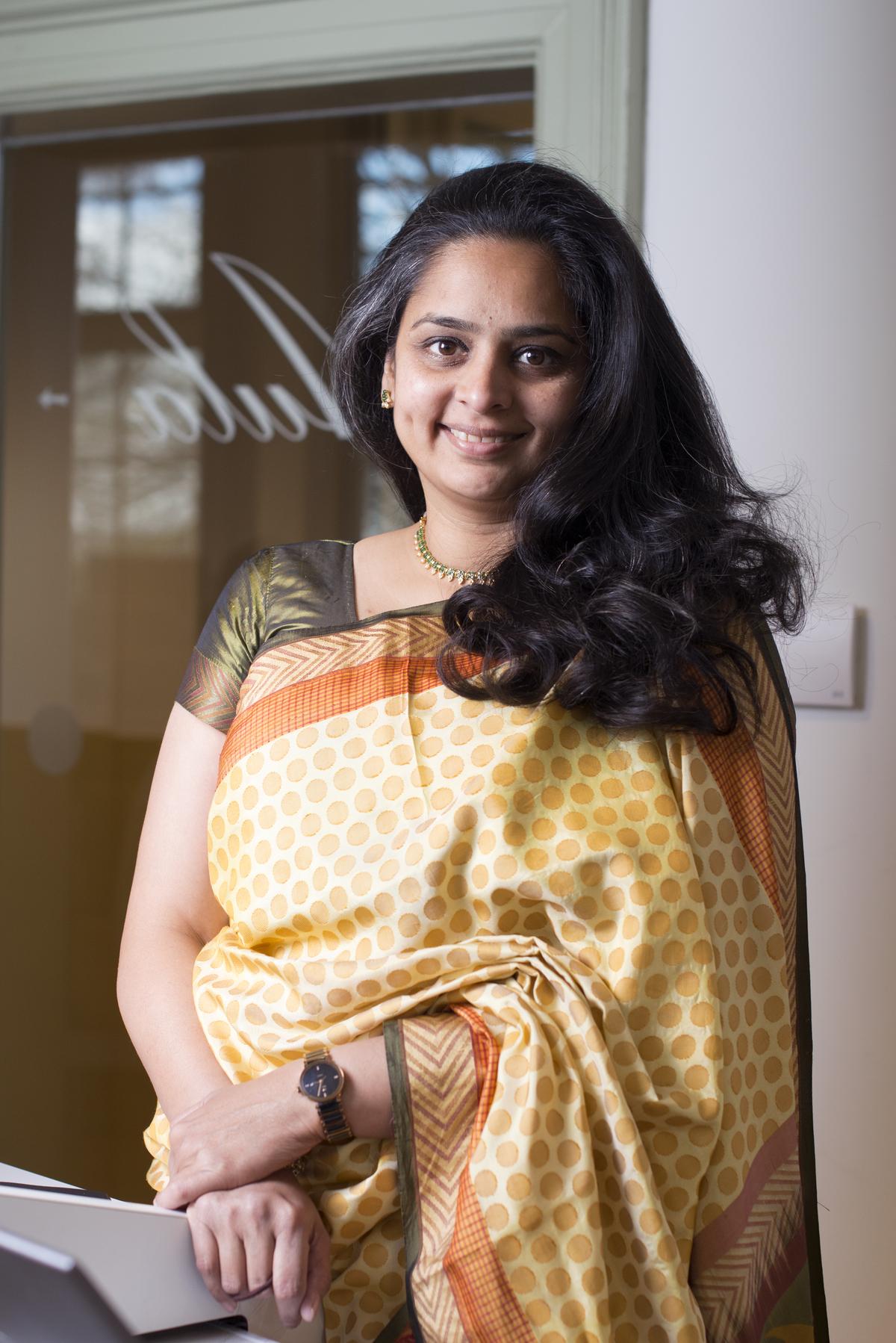

Abha Narain Lambah

That absence shaped her approach early on. “Conservation,” she argues, “cannot be limited to isolated buildings standing apart from social life. It must be understood as an urban, lived, and collective practice.” One of her earliest projects on Dadabhai Naoroji Road in Mumbai illustrates this ethos. Rather than treating the historic arterial street as a government-led beautification exercise, she worked directly with shopkeepers and residents, showing up week after week, talking through facades, materials, and identity. Over time, trust replaced suspicion. Eventually, 75 shopkeepers contributed from their own pockets towards restoring cobblestones, signage, and street character. It was conservation built not through authority, but through conversation — over many cups of chai.

The restored Victoria Public Hall in Chennai

“Most buildings cannot survive as static objects,” explains Lambah. “They need use.” Locked buildings deteriorate faster than inhabited ones: small cracks go unnoticed, water seeps in, roofs sag, pigeons and bats take over, and neglect compounds quietly. Occupied buildings, whether cultural centres or homes — are observed, maintained, and repaired. Their relevance extends their life.

Needs intervention: She often receives unsolicited messages from citizens suggesting future sites — “buildings waiting to be restored,” as one message put it, pointing to the Bharat Insurance Building on Mount Road. For Lambah, this quiet public yearning is the true measure of conservation’s success.

Aishwarya Tipnis, New Delhi

‘Family homes carry cultural value, too’

Recent project: Currently engaged in a conservation-led master plan for The Lawrence School, Sanawar, a historic hill-campus where heritage buildings, landscapes, and everyday student life are being treated as a continuous living system.

Once conservation moves beyond monuments, uncomfortable questions surface. Whose history is deemed worthy of protection? Who has access to conserved spaces? Who pays for upkeep — and who benefits from a building’s renewed visibility?

Tipnis, whose work often focuses on domestic and everyday heritage, argues that “heritage should not be restricted to royal lineages” or grand narratives. “Everyone has heritage,” she insists. “A middle-class family home, altered over generations, carries cultural value, too.” The problem is not lack of attachment — most people want to keep what they inherit — but lack of resources, time, and guidance.

Aishwarya Tipnis

Her approach emphasises care at an intimate scale. In projects such as the careful repair of a modest house in Old Delhi, working within tight budgets and with fragile Mughal-era bricks, Tipnis’ intervention is deliberately restrained. Cracks are stabilised, materials respected, and contemporary needs accommodated without visual drama. “When my design is invisible, conservation has succeeded,” she says. It is slow work: spending time with residents, understanding how people live now, and allowing the building to respond without pretending it belongs to another class, another century, or another imagination.

The drawing room of Seth Ramlal Khemka Haveli in Old Delhi after restoration

The Lawrence School, Sanawar

This ethos stands in contrast to both demolition-driven redevelopment and cosmetic heritage makeovers. It also foregrounds labour — craft knowledge, local skill, and long-term maintenance — as central to conservation’s ethics.

Needs intervention: Siliguri Town Station that’s a starting point for the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. “It’s dilapidated and abandoned, and actually a UNESCO World Heritage Site.”

Benny Kuriakose, Chennai

‘Tap into India’s living craft tradition’

Recent project: An over 200-year-old property in Ayyavandlapalle village, Andhra Pradesh. “It’s an interesting case study. The person restoring the jointly owned ancestral house has ‘first right to buy’ if one of the family members wants to sell their share. It’s a good model for heritage houses in places like Chettinad.”

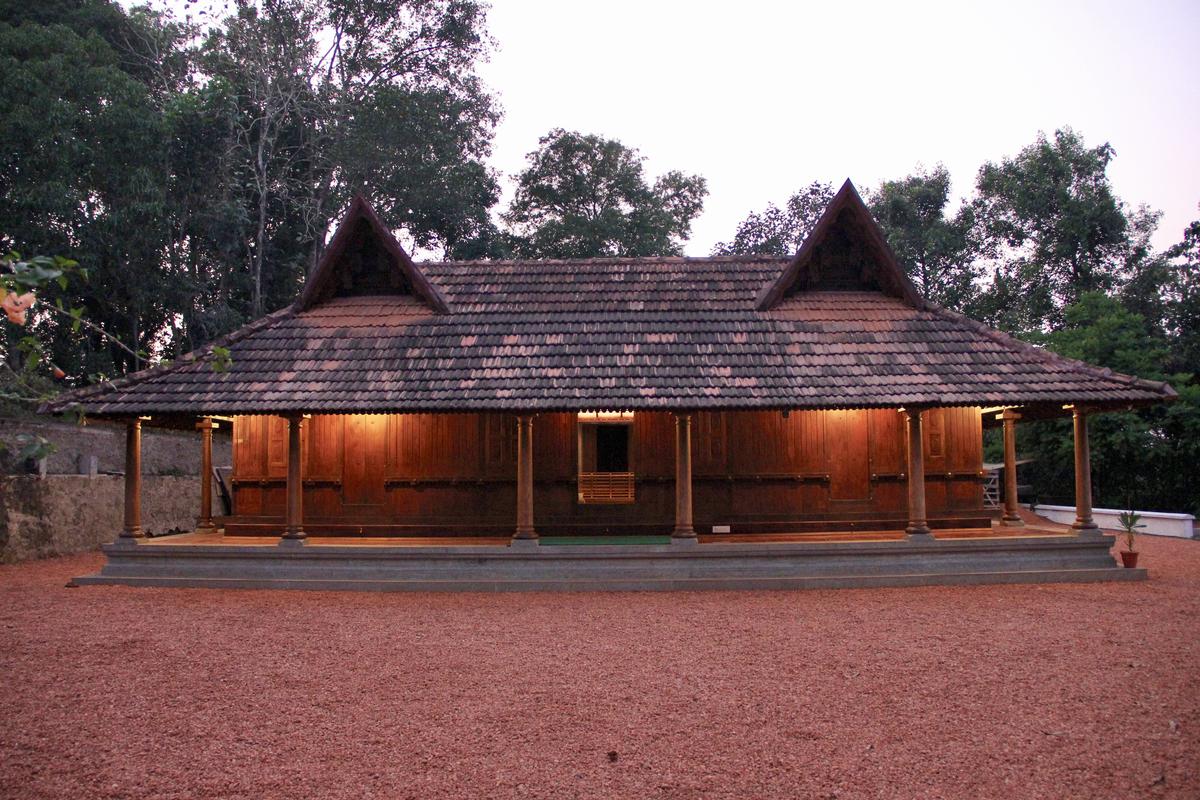

For Kuriakose, whose practice draws deeply from vernacular traditions and the legacy of architect Laurie Baker, conservation is inseparable from living systems. Vernacular buildings were never meant to last untouched for centuries; they were designed to be repaired, altered, and rebuilt. That cyclical understanding of time challenges modern obsessions with permanence and novelty.

Benny Kuriakose

“India still has a living craft tradition — masons, carpenters, tile-makers — whose knowledge is embodied rather than codified,” he says. “Conservation that relies solely on imported materials or technological fixes sidelines this intelligence.” Kuriakose’s work prioritises principles over style: climate responsiveness, local materials, skilled labour, and human comfort, while remaining pragmatic about contemporary needs. This is evident in projects such as The Bird at Your Window in Coimbatore, a residential development that draws from vernacular ideas of light, ventilation, verandahs, and landscape to create homes that reduce energy dependence.

Panicker House, an over 300-year-old house building with timber walls in Thiruvalla, Kerala, which was conserved.

This also reframes sustainability, and justice. Paying craftspeople fairly, valuing how work is done rather than how quickly it is completed, and designing buildings that reduce long-term energy dependence are political choices — even when they appear modest.

Needs intervention: “I’d like to see ordinary old buildings being conserved for the future. I have seen so many disappear in Mylapore and George Town in Chennai.”

Why should the public care?

This goes far beyond cultivating heritage pride as sentiment. It is about architectural literacy (learning to read materials and spaces), environmental intelligence (recognising that reuse is often more sustainable than replacement), and cultural humility (accepting that not everything new is better). When restored buildings are opened to the public — railway stations lit sensitively, theatres reopened after decades of closure — something shifts. The restoration of Mumbai’s Royal Opera House by Lambah is a case in point. Once shuttered and fading from public memory, its reopening allowed older generations to reconnect with a shared cultural landmark, while introducing younger audiences to a space they had never known. Conservation succeeds not when a building looks pristine, but when it becomes part of everyday life again.

Raya Shankhwalker, Goa

‘See modern heritage as meaningful’

Recent project: “In Puducherry, we completed the conservation and adaptive reuse of a Franco-Tamil villa [into a café-garden bar]. By re-establishing its relationship with the street, it sets a precedent that could encourage neighbouring owners to follow suit.”

Urban conservation rarely advances on expertise alone. It requires public pressure. Shankhwalker, known for his work in Goa and his role in heritage advocacy, emphasises that legislation often follows activism, not the other way around. Cities like Panjim benefited from early designation of conservation zones, but many Indian towns still lack basic frameworks to protect even significant modern heritage.

Raya Shankhwalker

“The recognition of Mumbai’s Art Deco precinct as a UNESCO World Heritage Site marked a shift not because the buildings were ancient, but because they forced a rethinking of value,” he says. “Modern heritage — cinemas, apartment blocks, civic buildings — does not wear the aura of antiquity. Its survival depends on people learning to see it as meaningful.”

Small interventions can have disproportionate impact. A restored rice mill in Morjim, completed in 2024, exemplifies this approach. Originally built in the 1950s, the mill was adaptively reused as a café-bar, with its architectural elements carefully restored. Glass inserts in the Mangalore-tiled roof allow natural light to filter in; everyday objects from the mill’s past were repurposed as elements of décor. Now functioning as a café and jazz venue, it demonstrates how a modest structure can retain its spatial essence while becoming a contemporary gathering place.

Hacienda de Bastora

The restored rice mill

In Puducherry, his careful undoing of insensitive renovations in a Franco-Tamil villa — such as restoring the characteristic pillars integral to the architectural style — re-established its relationship with the street, setting a precedent that encouraged neighbouring owners to follow suit. Conservation here works contagiously: one repaired building changes how others are perceived.

Entrance to the Franco-Tamil villa

Needs intervention: “The Massano De Amorim building in Panjim. Built around a large open ground, it needs urgent restoration as much for its architectural character as for its importance to the streetscape.”

The essayist-educator writes on culture, and is founding editor of Proseterity — a literary arts magazine.