My entry into the world of performative art and storytelling started when I was 10 years old. And that was solely because of my grandmother, who would watch three movies over a weekend. And, I was her main accomplice.

Post-dinner, we had these storytelling, singing, dancing and performance sessions for the kids [we all lived in semi-joint families] before going to bed. That was also the time when Sholay came to our town — my grandmother got addicted to the movie. Me too, particularly the scene where Dharmendra is on the water tank threatening to jump while proposing his profound love for Basanti, while the cool dude Amitabh Bachchan sits on the verandah sipping chai from a saucer with his denim jacket unbuttoned.

I wanted to be like Amitabh Bachchan. I wanted that denim jacket, that saucer, and that chai. After my continued insistence and prolonged tantrum-throwing, she managed to get me all three, but not exactly what we saw in the movie. After wearing the jacket and holding the saucer in my hand, I started transforming into the adult Amitabh.

Veenapani Chawla during an interaction on July 4, 2008.

| Photo Credit:

T. Singaravelou

My first audience was my grandmother, who was mightily pleased with my act. Then onward, she started suggesting my little act of Bachchan at every social event in our family. Thus began my journey to tell a story or become a storyteller.

Many years passed. I had the privilege of working with professional companies, performing street theatre, studying in a theatre institution for four years — yet somewhere, as an artiste, as a storyteller, I felt the tools I was using were not rooted and felt alien [maybe because of my exposure to the rich traditional performance culture I had grown up in]. These were random feelings that constantly niggled.

After my theatre studies, I joined a theatre group that enabled me to study martial arts and other traditional forms. This is where I met Veenapani, who had come to work with my director.

For the first few weeks, my interaction with Veenapani was limited [because of my lack of language skills and my inherent Mallu intellectual snootiness]. I thought what is she doing? Not even the revolutionary plays I was familiar with.

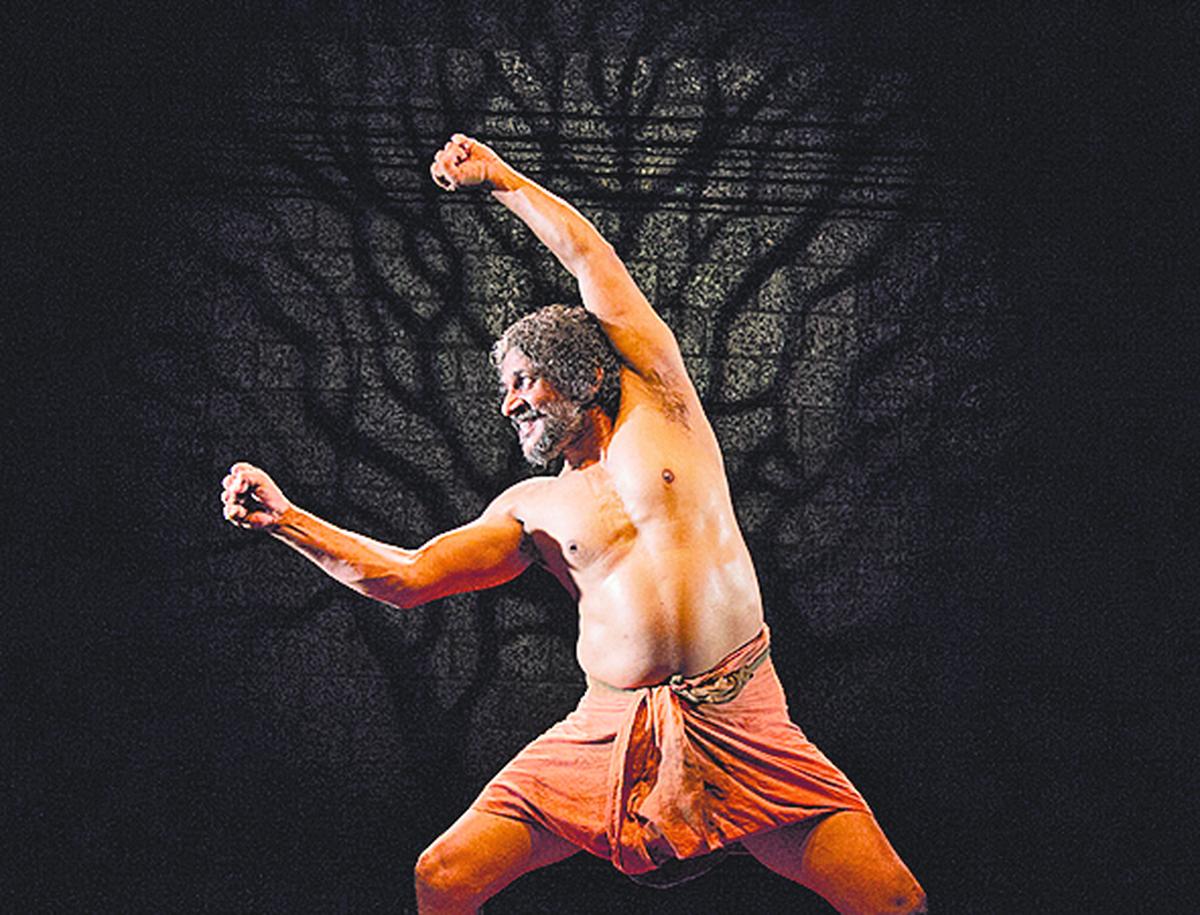

Artistic director Vinay Kumar

| Photo Credit:

S. S. Kumar

My love for Western classical music was at its peak then, but accessibility to titles was limited. I would travel any distance to get a copy of any music that was available. One day, Veenapani requested me to go to her room and pick up something she needed. Reluctantly, I went to the hotel with a friend, and when I opened her cupboard — what I saw changed my life.

A cupboard I expected to be filled with clothes was stacked with Mahler, Bach, Verdi, Requiem arias, and so on. I came back transformed, and saw Veenapani in a different light, with respect.

That day we had a conversation that lasted almost three hours. Both of us knew — I had found my guru, and she had found her subject/collaborator.

One agreement both of us had in the beginning of our journey was the magnetic effect of a traditional performer compared to a contemporary performer who relies too much on the intellectuality of their content. Our attempt was to look at the mechanics of varied traditional performances and create a unique Adishakti physical language on stage.

Artistes rehearsing at Adishakti for ‘Remembering Veenapani’ festival

| Photo Credit:

S.S. Kumar

Each of our plays — from Brhannala to Ganapati — became not mere productions, but research platforms that allowed Veenapani and me to expand the possibilities of the actor’s body and dynamism.

Years of this enquiry finally made it possible for us to create a performance methodology based on our investigation of breath, emotion, and anatomical structure.

Veenapani used to say — at the end of the year, if all of us [actors, creative people, staff, etc.] felt we had not grown emotionally or psychologically, then that collective was dead. And she made sure — as teacher, friend, and collaborator — we were all making that leap year after year.

Nimmy Raphel in the critically acclaimed Urmila

Post Veenapani’s demise — that was the one void we all felt enormously. But she used to say — “If I die tomorrow, you should all rehearse.” And that Herculean challenge is what fell on me.

We had three challenges at that time — one, instead of repeating Veenapani’s work, create a new artistic path for Adishakti’s second and third generation of creators. Two, make Adishakti an economically self-sustainable organisation. And three, take Adishakti from a closed-in research space to a wider world where more artistes and communities feel ownership.

From Adishakti’s popular production ‘Bali’

Along with my collaborator and the current managing trustee of Adishakti — Nimmy Raphel — we took the challenge head-on.

Today, when I look back — we have become a self-sustaining institution for the last 9 years. We have been able to create widely appreciated plays such as Nidravathvam, Bali, Bhoomi, Urmila, Heros, etc.

This month of April, we are gearing up for our annual festival — Remembering Veenapani — a multi-disciplinary arts festival now in its 11th edition.

When Veenapani’s birthday came after her untimely demise, we at Adishakti thought — instead of mourning, we should celebrate her work, vision, and her as a human being. That’s where the idea of the festival came from.

When we contacted multiple artistes, they all said — don’t worry about money, we will come and perform [at that time we didn’t have any money].

From there on, Remembering Veenapani became one of the most sought-after festivals for many artistes and spectators.

It’s a unique event — without the usual festival trappings — and primarily focusses on the performer. And we are all hoping that we continue this focus in the unique experience a performer can bring.

Published – April 09, 2025 06:15 pm IST