GUWAHATI

Scientists from the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) have resolved longstanding taxonomic ambiguities surrounding South Asian treeshrews – small, insectivorous mammals often misidentified due to their superficial resemblance to squirrels. Drawing upon century-old specimens housed in national collections, the study offers fresh insight into the morphological diversity of these elusive creatures.

Their study was published in Ecology and Evolution, an international journal, on Friday (April 25, 2025). The authors of the study are Manokaran Kamalakannan, Mukesh Thakur, Nithyanandam Marimuthu, Subhojit Pramanik, and Dhriti Banerjee.

Treeshrews are neither true shrews nor squirrels, but belong to a distinct order called Scandentia. While they share a similar size and arboreal lifestyle with squirrels, treeshrews can be easily distinguished by their elongated snouts, reduced whiskers, moist nasal pads, and insectivorous or frugivorous diet.

Historically misclassified as primates, the treeshrews – some arboreal, some semi-arboreal, and others terrestrial – are now recognised as an ancient lineage of mammals endemic to South and Southeast Asia.

Dr. Kamalakannan, the lead author and scientist at the ZSI’s Mammal and Osteology Section, conceptualised and led the study from data collection to the final morphological analysis. “By examining decades-old museum specimens, we have shed light on how these fascinating mammals differ from one another,” he said.

“This clarity is essential for accurate species identification and for shaping effective conservation policies. When analysed with modern techniques, museum specimens reveal patterns of variation that were previously hidden, helping us address long-standing taxonomic ambiguities,” he said.

Co-author Dr. Marimuthu, who led the complex multivariate analyses, said: “The morphometric patterns we uncovered offer strong statistical support for separating these species, which were once thought to overlap significantly in size and shape.”

Most strikingly, the study overturns long-standing assumptions about the Nicobar treeshrew. Once believed to be the smallest among South Asian treeshrews, the analysis reveals it is the largest in South Asia and the third-largest of all 23 known treeshrew species globally.

More research advised

“There is a need for genetic studies to support a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of South Asian treeshrews. This should be a priority for future research,” Dr. Thakur, another co-author, said.

Dr. Banerjee, also the Director of ZSI, underlined the implications of the findings. “This study is a major step forward in mammalian conservation in South Asia. Accurate taxonomy is fundamental to protecting species, particularly insular endemics like the Nicobar treeshrew, which faces growing ecological pressures,” she said.

The research utilised a wide dataset from South Asian treeshrew specimens preserved for over a century at the ZSI’s National Zoological Collections, a repository of India’s faunal diversity, in Kolkata.

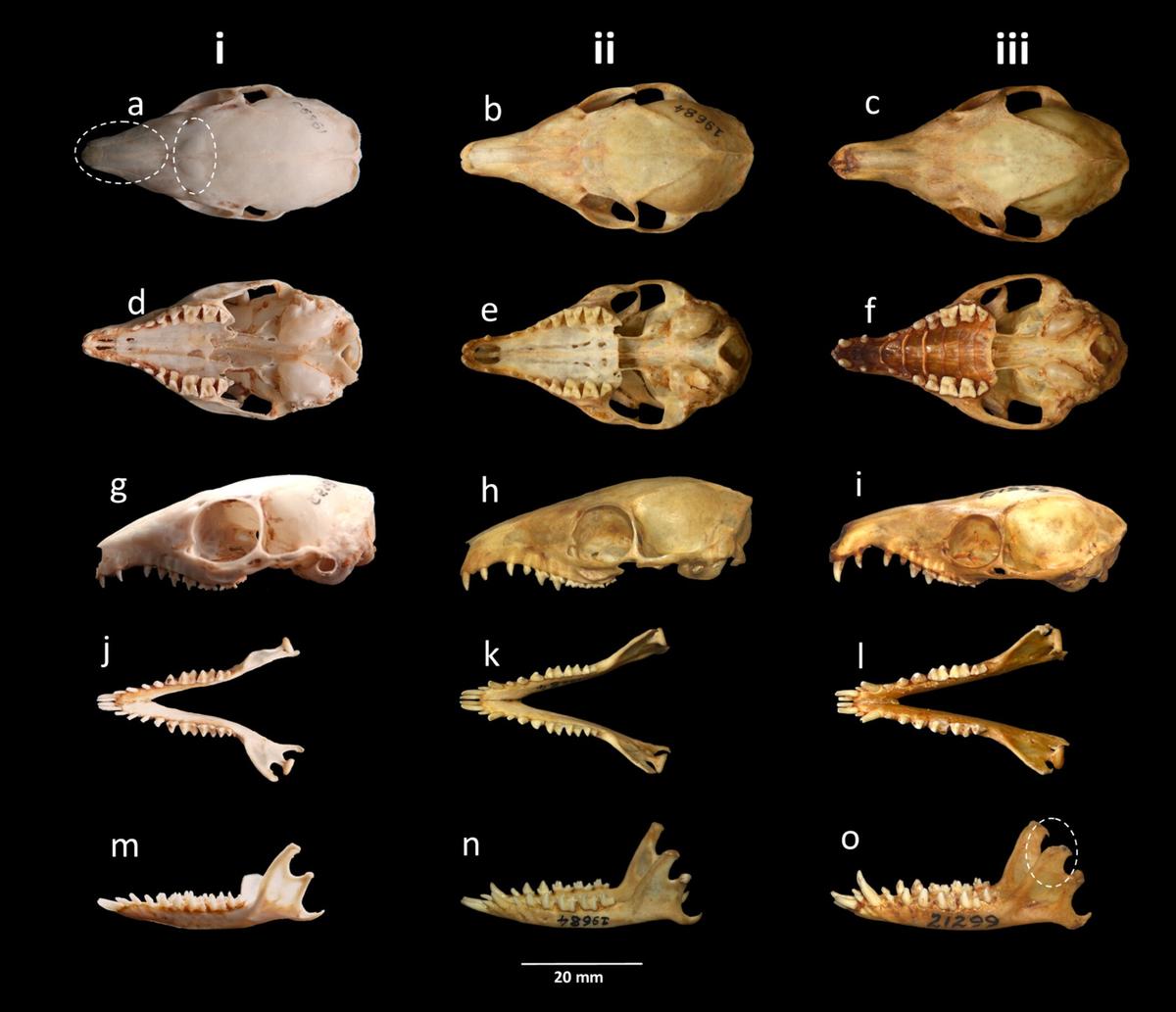

The scientists investigated the morphological variation among three species – Madras treeshrew (Anathana ellioti), northern treeshrew (Tupaia belangeri), and Nicobar treeshrew (Tupaia nicobarica) – using museum specimens collected over a wide spatial and temporal range of India and Myanmar and combined with existing published datasets.

These three species occupy distinct and non-overlapping geographical areas in India and Southeast Asia.

The scientists analysed 22 cranial measurements and four external traits to evaluate inter- and intraspecific morphological differentiation, employing distance-based morphometric approaches validated by multivariate analyses. Their findings revealed considerable heterogeneity in cranial morphology, with three species exhibiting clear differentiation, despite slight overlaps in morphospace.

Published – April 25, 2025 04:21 pm IST