Hello and welcome to the last Weekly Vine of the year.

This is the week when editors everywhere are expected to turn briefly into poets. To summon W.B. Yeats. To cast a cold eye. To pretend that twelve chaotic months can be neatly flattened into insight. It is a noble impulse, and like all noble impulses, largely pointless, a bit like Sisyphus pausing halfway up the hill to wonder if the boulder has learned something new this time.

Frankly, the only thing I learned this year was that at my age, even eating a chole bhatura can be considered an adventure sport, with rather perilous consequences.

Hence, we will avoid any such Yeats-like musing and just spin the wheel one last time. In this edition, we trace how anti-India sentiment went mainstream in America, hand the Designer of the Year Award to Generative AI, decode the meltdown over Stranger Things, and point out why reports about the death of velocity journalism are greatly exaggerated.

Uncle Sam normalises anti-Indian hate

There are bad stoner movies, good stoner movies, and elite stoner movies. Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle firmly falls in the third category, the first proper coming-of-age movie that shows that second-generation Asian-Americans are just as assimilated as other races and have the same American dream: getting high, meeting girls, and binging on hamburgers.

What set Harold and Kumar apart was that it showed the Asian experience wasn’t that different from the American one, epitomised by the scene where Kumar explains to Harold, while urging him to paraglide to a White Castle outlet, that their immigrant parents had come here because they were hungry, providing an adequate noughties update to the American dream.

For a long time, Indian-Americans believed their story was headed there too.

Not to White Castle specifically, but to a sort of “white castle”: where you are so integrated and assimilated that you are considered a beacon of society, an upstanding member of the Shining City on the Top of the Hill. A place where your faith was acceptable, like all the other faiths that existed in the American tapestry.

And then one Hanuman statue in Texas shattered that carefully crafted delusion.

The statue, built on private land, became a reminder that America’s promise of welcome often frays the moment difference stops being discreet. Even as Vande Mataram and The Star-Spangled Banner played on temple grounds, conservative Christian protesters gathered outside, denouncing Hanuman as a “demon god”. One local politician asked publicly: “Why are we allowing a false statue of a false Hindu God to be here in Texas? We are a CHRISTIAN nation.”

Srinivasachary Tamirisa, a doctor who spent decades practising in the United States and quietly supported the statue project for more than twenty-five years, told The New York Times that he once viewed the country as a kind of promised land. When confronted by protesters, he said he tried to explain the figure they were objecting to. To him, Hanuman was not a demonic symbol but a spiritual guide, one meant to convey courage rather than fear.

But perhaps what has been disquieting Indian-Americans isn’t the protest. America has always had its fair share of protesters, a right enshrined in the First Amendment. The tragedy was the timing, which neatly folded into the rise of anti-Indian sentiment, online and offline, often juxtaposed with gleeful Hinduphobia.

Just when Indians thought they were in, the newest adherents promising to make America great have been mainstreaming anti-Indian sentiment. To put it frankly, this wasn’t how it was supposed to be.

Designer of the Year: Generative AI

In The Matrix Reloaded, Morpheus, after his ship the Nebuchadnezzar is sunk, makes a biblical reference: “I have dreamed a dream, but now the dream is gone from me.” The line became shorthand for the disappointment of hardcore Matrix fans who watched the pathbreaking original dissolve into bubble-gum pulp fiction sequels. It is also a sentiment shared by those who have spent years waiting for the arrival of the deus ex machina of Artificial General Intelligence.

Cinema trained us to expect Agent Smith or the Terminator. What we got instead were malfunctioning interns who forget their brief after three prompts, which is not entirely unlike regular interns. If there is one area where artificial intelligence has genuinely altered daily life, for better or worse, it is generative AI.

Generative AI has undeniably made certain tasks easier. Research is faster. Summaries are cleaner. Editing copy is less painful. For writers, it offers something rare: an unbiased copy editor that does not inject its own ideology into the text. And even if large language models never write great literature, they produced something unmistakable this year: genuinely good images.

With the right prompts, the prompt engineer briefly became an amalgamation of Vincent van Gogh, Salvador Dalí, and Bill Watterson. While Time magazine crowned “AI Architects” as its Person of the Year, we believe artificial intelligence quietly earned another title: Designer of the Year.

Queer Things?

It must be exhausting to live as a permanently mobilised political activist. MAGA or woke liberal, the job description is the same: wake up, scan the internet, locate a fresh provocation, and perform outrage before lunch. Peace is not an option. Calm is counter-revolutionary. Meaning must be extracted from Netflix shows at gunpoint.

This week’s cultural emergency, for the MAGA internet at least, is Stranger Things.

The latest threat to WENA civilisation has arrived via Hawkins in the form of queerness, competent women, and the unpardonable sin of a television show refusing to freeze itself in 2016.

To be clear, there are plenty of legitimate criticisms to make about Stranger Things Season 5.

The gaps between seasons have been absurdly long.

The nostalgia has become self-cannibalising.

The kids no longer look like kids, which creates the odd effect of watching fully grown adults play Dungeons & Dragons with the emotional urgency of middle schoolers.

Millie Bobby Brown now looks less like a supernatural child on whom the government carried out illegal experiments and more like a GOP candidate who will carry out said illegal experiments on other children.

Vecna, once genuinely unsettling, has suffered from the Marvel villain problem. Too much screen time. Too much explanation. Too little mystery. The show has run so long that most of its Easter eggs now land only for people who maintain annotated timelines and Reddit spreadsheets.

But none of this is what enraged MAGA.

What truly broke the internet was the confirmation of something Stranger Things had been gently telegraphing since its earliest seasons: Will is gay. And not just gay, but emotionally central. Worse, narratively powerful. Even worse, capable of influencing Vecna and his hive mind.

This, apparently, is where storytelling crosses into propaganda.

The MAGA critique is not subtle. Netflix, they insist, has “ruined” a classic by injecting queerness and “girlbossing” into what was once pure, wholesome entertainment. That Will’s arc was always headed here does not matter. That his queerness was written with restraint rather than spectacle does not matter. What matters is the confirmation of a worldview in which every cultural product is either recruiting or resisting.

Nancy Wheeler being a competent shooter is treated as ideological subversion. Mrs Wheeler standing up for her children becomes feminist indoctrination. Liberated women are not characters. They are symbols. And symbols, in this worldview, exist solely to humiliate men.

This is less a critique of Stranger Things than a confession.

Because what MAGA is reacting to is not the presence of queer characters or capable women. It is the loss of narrative monopoly. The real fear is not that culture has changed, but that it no longer pauses to ask permission.

Pop culture, once a comforting mirror, has become an independent organism. It reflects society as it is, not as one faction would prefer it to remain frozen. And for people who need entertainment to validate their identity rather than complicate it, that is intolerable.

Stranger Things didn’t suddenly become political. The audience did. And now every monster, metaphor, and mullet must be pressed into service.

In the end, the Upside Down isn’t Hawkins. It’s the internet.

Postscript by Prasad Sanyal: The end of volume or velocity journalism has been announced before…

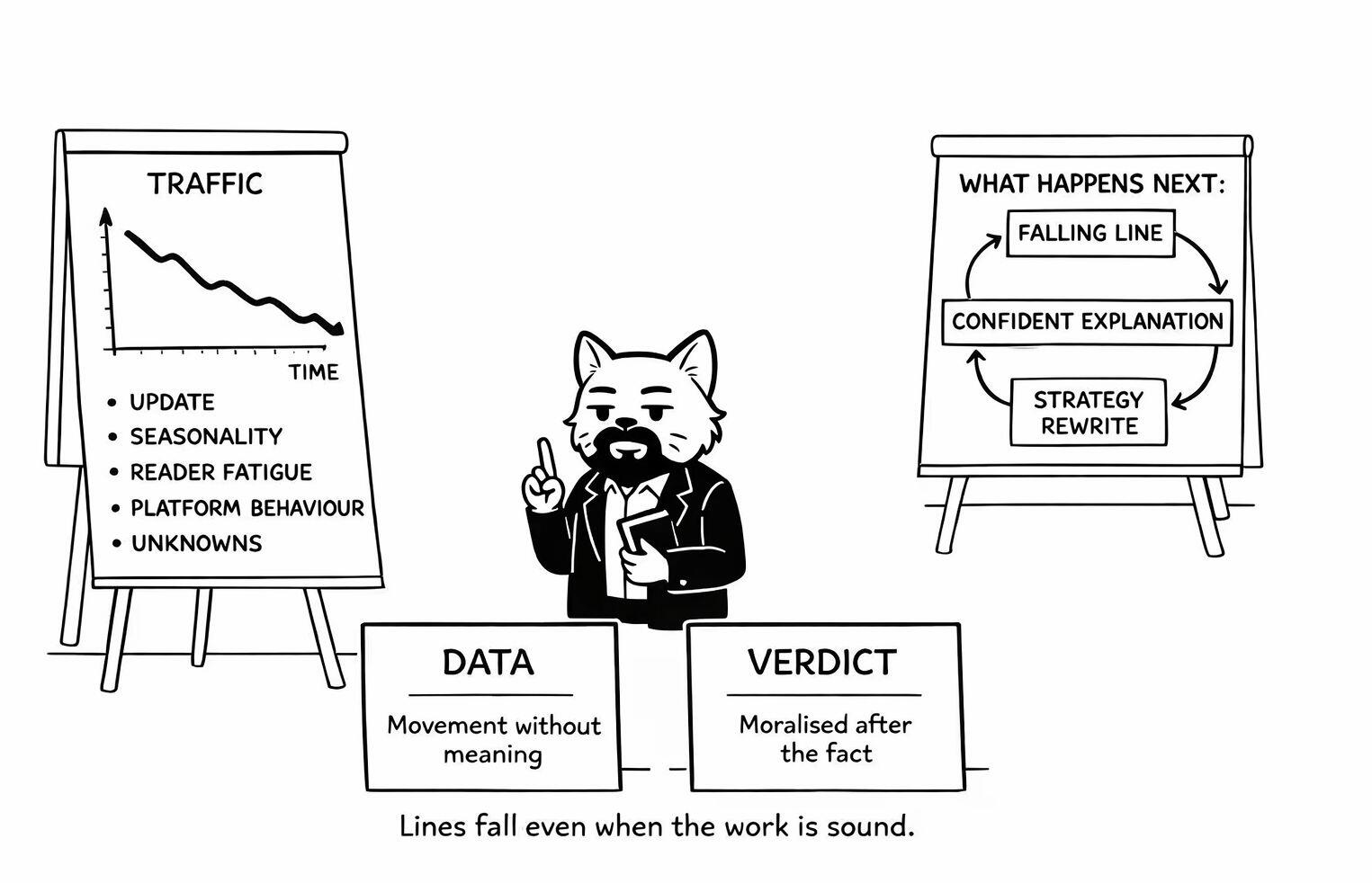

I spent these December weekends doing what digital editors now perhaps do on long weekends: watching lines fall.

Traffic charts, update notes, before-and-after comparisons, the familiar ritual of trying to locate meaning in a graph that refuses to explain itself. Somewhere between the third dashboard refresh and the fourth theory, Sahir Ludhianvi drifted in uninvited, as he often does when certainty begins to wobble. “Khwaab ho, tum ya koi haqeeqat.” Are we looking at a dream, or at something real?

Every algorithmic update arrives with its own sermons. This one speaks in the language of meaning. Not keywords, not brute scale, not the velocity with which newsrooms push stories into the world, but something more elevated: semantic depth. The machine, we are told, now understands ideas, nuance, and context. And from this understanding flows a familiar promise, delivered with great confidence. Volume or velocity journalism will finally be punished. Fewer stories, deeper thinking, harder-to-summarise work will be rewarded.

It is an attractive idea, especially when you have just watched traffic dip for reasons no one can fully explain. It flatters editors who have always believed that the problem was never journalism, only distribution. It reassures long-form writers who have survived one too many conversations about output and efficiency. It offers the hope that the dashboards might one day align with our better instincts.

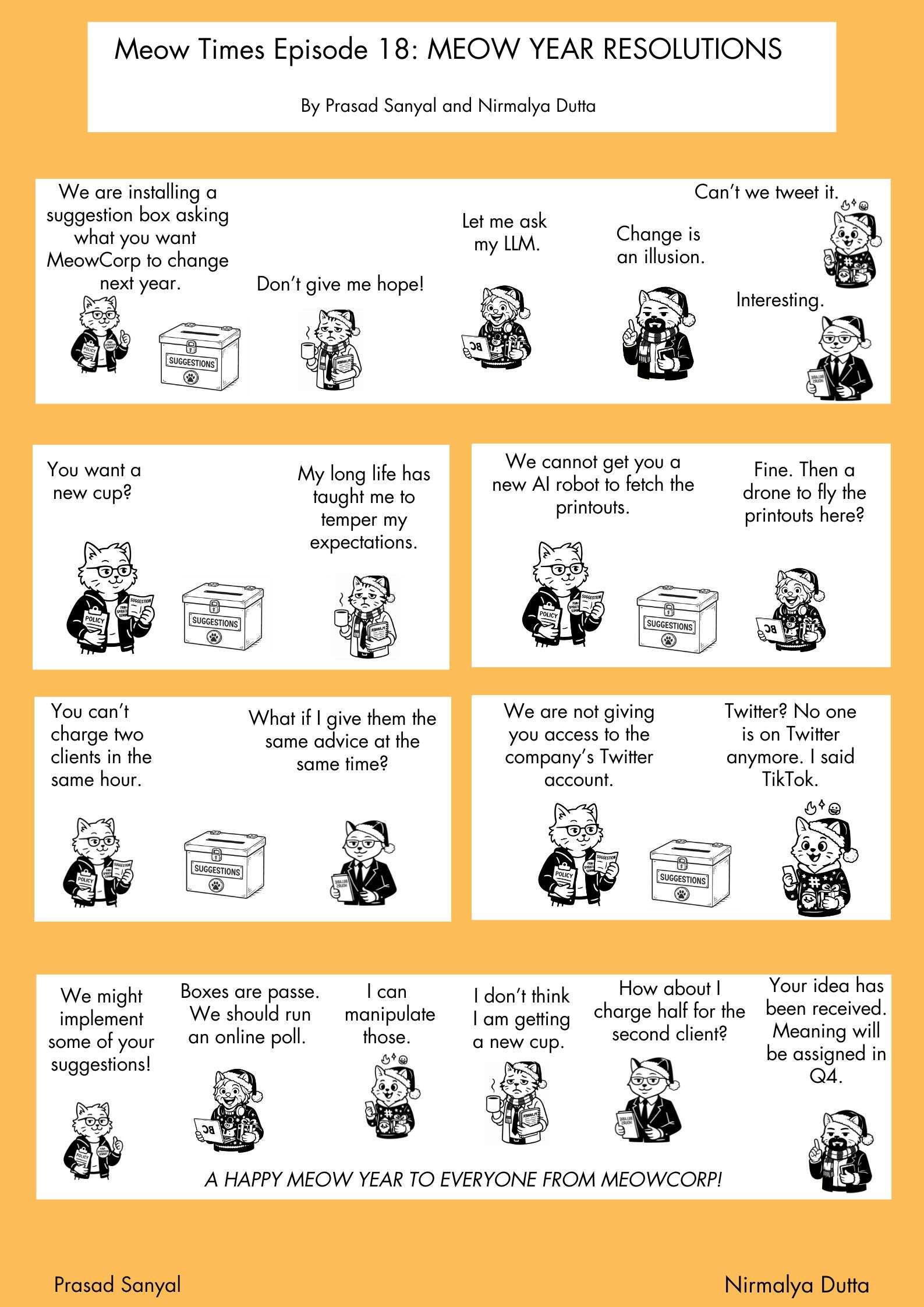

Happy Meow Year

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE