“If we are not able to adhere to this lockdown sincerely for 21 days, believe me, India will go back 21 years,” warned Prime Minister Narendra Modi on March 24, 2020, as India registered 10 deaths due to the spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19). Implementing a total lockdown where in all government offices, educational institutions, places of worship, private offices, establishment were shut down, Mr. Modi allotted ₹15,000 COVID-19 fund for purchase of personal protection equipment (PPEs), setting up testing labs, quarantine centres and expanding hospital facilities to tackle the rising cases.

Five years have passed since India implemented the strictest lockdown, saw the steepest rise in COVID-19 cases and fatalities, a steep dip in its economic growth before it gradually loosened its lockdown restrictions as cases receded.

Here’s a timeline of India’s lockdown-unlock journey:

2020

March

As the first few cases of COVID-19 began in India, its virulent nature forced India to begin screening, isolating, quarantining the affected persons and tracing their contact history. In a bid to give India’s healthcare system, medical professionals, sanitation workers, scientists and others time to prepare for the rising COVID-19 cases, restrictions on assembly of people were first imposed in Kerala, Delhi and Maharashtra. Denying any ‘community transmission’ of COVID-19, Centre first imposed a 14-hour lockdown called ‘Janata Curfew’ on March 22, 2020 to break the spread. However, within two days, it was evident ‘Isolation is India’s best weapon’, as opined by then-ICMR chief Dr. Balram Bhargava.

After Janata Curfew, renowned Indian economist Jean Dreze warned, “A double crisis looms over India: a health crisis and an economic crisis,” in The Hindu’s column. “Migrant workers, street vendors, contract workers, almost everyone in the informal sector — the bulk of the workforce — is being hit by this economic tsunami,” he explained, urging Centre and States to make good use of existing social security schemes to support poor people, creativity in shutting public services to limit economic damages and warning “sectors of the economy will soon be lobbying for rescue packages”.

“Draw a Laxman Rekha outside your house door and do not step outside of it. Stay where you are,” instructed Mr. Modi in his televised address on March 24, 2020, announcing a full lockdown for 21 days. Shops providing essential products like food, groceries, dairy, fruits and vegetables, meat, fish; banks, media houses, telecom services, medical shops, petrol pumps, power services, cold storage and warehouses were the only ones which remained open. Strict curfew timings were put on movement of people and only essential workers – medical workers, sanitation workers, power, telecom, post, food delivery workers, media and emergency response workers were allowed to venture out.

Dr. Dreze’s warning came true within days of the total lockdown. Ahead of the swift imposition of lockdown on March 21, 2020 in Mumbai, hundreds of migrants thronged Lokmanya Tilak Terminus, attempting to board trains travelling back to their homes in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar. “Visuals of hundreds of workers wearing gamchas, carrying heavy backpacks and wailing children, and walking on national highways, boarding tractors, and jostling for space atop multicoloured buses became defining images for days to come in India,” reported The Hindu, as total lockdown forced migrants to trudge back home on foot.

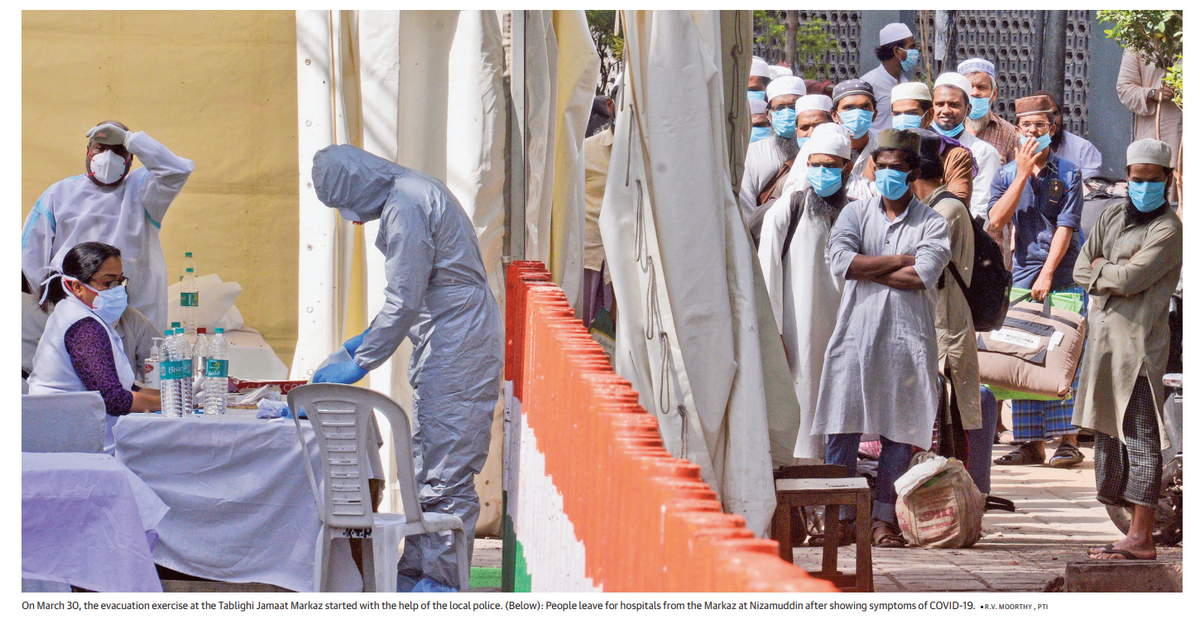

As lockdown was imposed, 4,500 people who had attended a convention of a conservative Islamic organisation – Tablighi Jamaat – at its headquarters in Delhi, had travelled across India. With most travellers testing positive for COVID-19, police was tasked with tracing their contacts, isolate them and treat them. The convention became India’s first ‘COVID-19 cluster’ as several thousand travellers were stuck in Markaz, necessitating their safe evacuation, screening, isolation and treatment. As Muslims across India faced the ire on social media over the Tablighi Jamaat incident, Maharashtra CM Uddhav Thackeray promised strict action against those spreading communal violence.

April

The 21-day lockdown was extended as COVID-19 infection spread across India with the Centre announcing a ₹1.7-lakh crore stimulus package, free gas cylinders, increase in MGNREGA wages, cash stimulus of ₹1,500 via Jan Dhan accounts. “Top 1% of India held 62% of all currency in circulation,” opined economist Appu Esthose Suresh in The Hindu, stating that a targetted ₹2.5 lakh-crore cash transfer was necessary to the cash-striven citizens. “₹1.34 lakh crore will be for the poorest 500 million Indians, whereas ₹1.2 lakh crore will replenish the reduced cash reserves of the rest”.

On extension of lockdown, the southern States — Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Karnataka — opted to undergo massive testing to aide better contact tracing and isolation. The States also expanded the number of beds available in COVID-19 centres, offered cash transfer for poor families, farming families, daily wagers — all who had lost jobs and incomes. Meanwhile, Punjab and Haryana, which was experiencing a bumper crop in April-May, faced a dearth of labourers due to lockdown. With the closure of all transport facilities and most migrant labourers gone back home, farmers lost most perishable crops and struggled to store foodgrains.

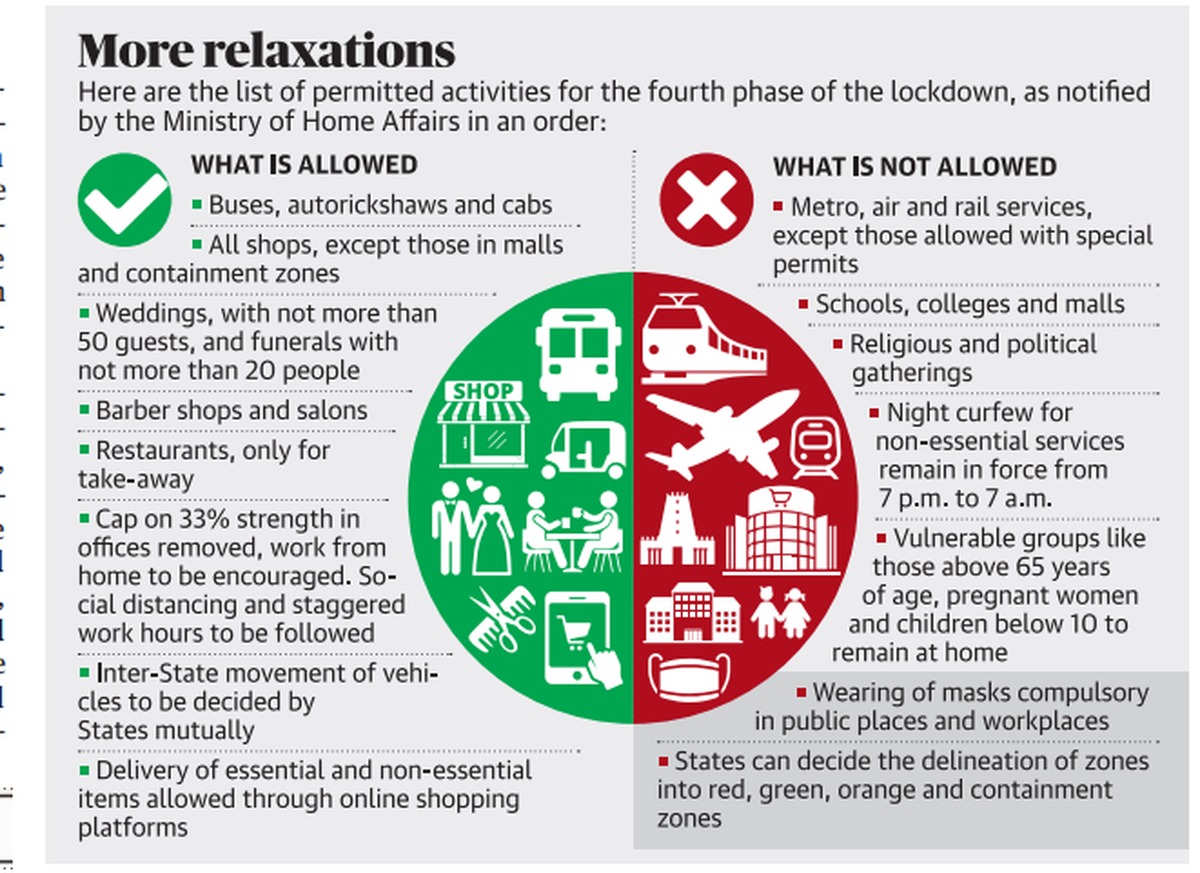

May

In the third phase of lockdown, metro, rail and air services remained shut, educational institutions, social gatherings remained banned. However, buses, autorickshaws and cabs were allowed to ply and shops, restaurants outside containment zones were opened up. States had more autonomy to decide on infection zones. Capping strength in offices to 33%, interstate transport was allowed (mutually agreed upon by states) and online delivery of goods was allowed again. As the Centre plied ‘Shramik trains’ to allow migrants return home, states began opening up their borders and issued guidelines for opening up various businesses, establishment, offices.

By the end of May 2020, lockdown had been extended for the fourth time, but not for the complete nation. Focusing on 13 cities which had recorded 70% of the total COVID-19 cases, Centre imposed strict curbs on Mumbai, Chennai, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Thane, Pune, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Indore, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Chengalpattu and Thiruvallur. However, States were allowed what could remain open in the remaining areas, except metro trains, restaurants and malls which continued to remain shut.

Exceptional success stories emerged from across India in containment during the lockdown. Rajasthan’s ‘Bhilwara model’ inspired the Centre’s cluster containment model which involved effectively sealing the district from other areas. Bhilwara officials had isolated the initial 26 cases reported and placed the hospital along with its staff in lockdown, halting the virus’ spread to nil by end of April. In contrast, in Dharavi – Asia’s largest slum, home to 3.6 lakh people per sq. Km, social distancing was not feasible. The municipal authorities undertook the most rigorous testing, contact tracing exercise to curb its spread. Dharavi managed to beat the COVID-19 curve by end of July due to its strict containment measures, testing and isolation.

However, loopholes in various’ States testing and contact tracing methodology emerged by May. ICMR found that Kerala was testing 40 contacts per confirmed COVID case, while Maharashtra was testing only eight contacts. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Goa, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand had tested atleast 75% of the contacts of every COVID-19 case, while Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi were among those with less than 50% contacts tested.

June-December

Unlocking of the country began during these months in phases. Buses, trains, metro trains became fully operational as did shops, businesses, agricultural and trading activities. The first wave of COVID-19 appeared to be declining as the country opened up.

However, by July, Kerala once again started recording a spike. While the State had successfully curbed its initial cases leveraging its epidemic management skills due to two Nipah outbreaks, cases began to rise as curbs relaxed and public movement increased. With people violating social distancing curbs, community transmission of the virus began in pockets of Thiruvananthapuram, reported The Hindu. Fearing another lockdown, people grew restive until the State government announced relief measures dipping into emergency funds. The Centre was still maintaining that community transmission was not prevalent across India.

Another State which lost its control of its COVID-19 strategy was Telangana. Then CM K. Chandrashekhar Rao had initially downplayed the virus’ infection rate, not allowing private testing centres or private hospitals to treat cases. As citizens moved courts seeking relief, Mr. Rao imposed the toughest lockdown measures. However, lack of transparency in testing, screening, contact-tracing and even reporting fatalities, punched holes into Telangana’s COVID strategy as cases began rising.

By the end of the year, Centre began celebrating that ‘India had triumphed over COVID’ as two vaccines gained authorisation for public roll-out. While several States, medical officials begged people to maintain social distancing and use masks, pre-emptive celebrations of ‘normalcy’ were witnessed across India. Minimal lockdown was imposed across India and guidelines to safely reopen schools were being framed.

2021:

January-February

Five States were scheduled to go to polls in April-May 2021 – Tamil Nadu, Assam, Kerala, West Bengal and Puducherry. As healthcare and other frontline workers began receiving their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, political campaigning began with full vigour. Large rallies where social distancing norms were not being followed, roadshows with thousands in attendance, unmasked crowds standing in close quarters became a regular spectacle. Top leaders including PM Narendra Modi, party chiefs Mamata Banerjee, M.K. Stalin, E Palaniswami and others were seen holding such rallies across cities were COVID-19 cases were rampant.

In this March 7, 2021, file photo, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporters wear masks of Prime Minister Narendra Modi as they gather for a rally addressed by Modi ahead of West Bengal state elections in Kolkata, India. India’s death toll from COVID-19 has surpassed 200,000 as a virus surge sweeps the country, rooted in so-called super-spreader events that were allowed to happen in the months following the autumn when the country had seemingly brought the pandemic under control

Two new COVID-19 variants — Delta and Omicron had been discovered in some of the newly reported cases. Both variants were found to be more virulent and its symptoms more serious. Signs of an emerging COVID-19 wave in the upcoming months were evident.

March-April

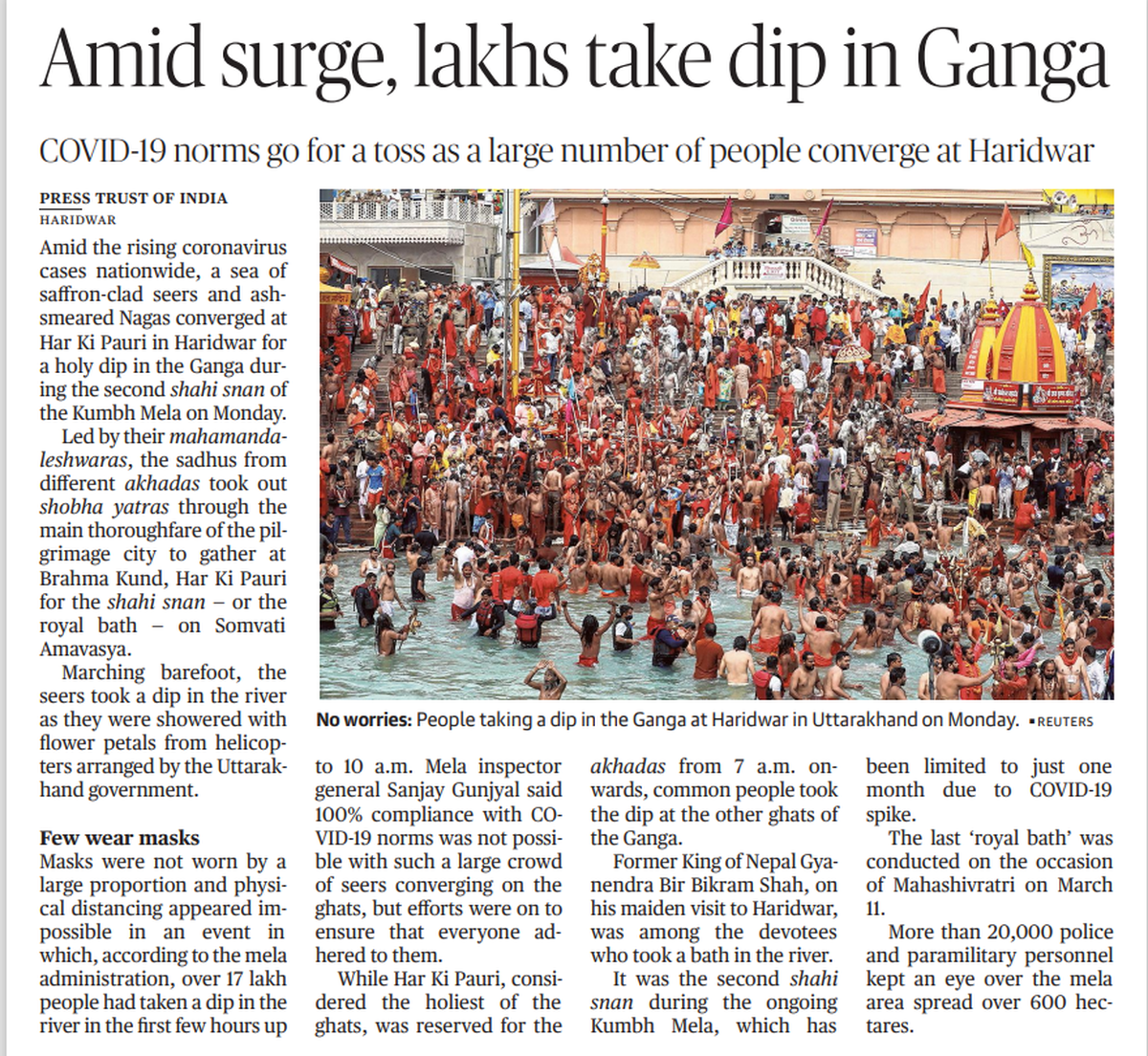

Inspite of a ban on mass gatherings, the Centre and Uttarakhand government went ahead with the Haridwar Maha Kumbh Mela in March-April. The country watched in horror as lakhs of saints, devotees flocked to take a dip in the Ganges. Uttarakhand’s new CM Tirath Singh Rawat had stated that a negative COVID-19 test wouldn’t be a requirement, leading to COVID-19 norms going for a toss. Cases began surging across the gathering with several seers began testing positive for COVID-19 with Mahamandleshwar Kapil Dev Das dying due to the virus. With inadequate test kits in hand, lack of isolation centres and hospitals, the akharas soon announced end of their participation.

As India’s COVID-19 daily tally touched 2.3 lakh cases on April 18, 2021, Mr. Modi urged the seers to end the event and undergo the remaining the rituals at their homes. However, by then, the second wave of COVID-19 was washing across India.

Maharashtra and Delhi were forced to reinforce strict lockdown measures as cases, fatalities spiked in these states. Stretched to its limit, hospitals across Delhi were struggling with a shortage of medical oxygen and hospital beds. Maharashtra closed down its restaurants, malls, auditoriums and all mass gatherings were banned. All offices were forced to cut down strength to 50% while government offices too were reduced to only elected representatives’ attendance. Both States continued these curbs well into May as number of cases due to the Delta variant of COVID-19 spiked.

With more 3 lakh cases being reported daily, India watched as relatives grappled to procure oxygen for their loved ones in Delhi hospitals, thousands of bodies emerged across the Ganga in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh – highlighting the nation’s ineffective strategy to counter the second wave. Inspite of the Allahabad High Court’s orders, Uttar Pradesh government refused to impose a complete lockdown in major cities, opting for a weekend lockdown.

In this May 8, 2021, file photo, Indians wait to refill oxygen cylinders for COVID-19 patients at a gas supplier facility in New Delhi, India. The capital of New Delhi is seeing some improvement in the fight against the coronavirus, but experts say the crisis is far from over in the country of nearly 1.4 billion people. Hospitals are still overwhelmed and officials are struggling with short supplies of oxygen and beds

“The government took almost no steps to limit the risk posed by the Kumbh Mela festival, ironically claiming that infection precautions would present too great a threat to crowd safety,” opined health expert Dr. Ashish K. Jha in The Hindu. He added, “The virus has taken advantage of the overconfidence of the government over the past months, making matters worse. With far too cases being analysed, India must rapidly scale up its genomic surveillance efforts to give scientists the data they need to guide policy decisions”. He batted for surge in testings, mandatory masking, ban on all mass gatherings and ramping up vaccination.

May onwards

As India ramped up its vaccination drive in May, States which had re-imposed lockdown norms during the month, began relaxing it. By end of July, COVID-19 norms had been fully relaxed and vaccination was taken up on war-footing by States. Centre ruled out a third wave as cases reported daily dropped down and vaccination rates increased.

(With inputs from Hindu Archives)

Published – March 26, 2025 10:19 pm IST